Compare Any Hair Loss Disorder

Get a close-up view of the progression of the four major hair loss disorders.

Juvenile hairline with no evidence of recession or diffuse thinning. All scalp regions show less than 20% hair diameter diversity (i.e., hair follicle miniaturization) – with hair follicle clusters producing 2-5 hairs per cluster.

Full hair density, with no evidence of hairline recession or diffuse thinning. All scalp regions show less than 20% hair diameter diversity (i.e., hair follicle miniaturization) – with hair follicle clusters producing 2-5 hairs per cluster.

Slight hairline recession beginning at the temples. Hair diameter diversity is greater than 20% and hair follicle clusters now produce 1-3 terminal hairs.

A decrease in hair density and anagen:telogen ratios may already present across the scalp, even without cosmetic levels of hair loss.

Slight diffuse hair loss across the scalp, often represented through a “widened” hair part. Hair diameter diversity is greater than 20% and hair follicle clusters now produce 1-3 terminal hairs.

Diffuse thinning across the entire scalp, often most notable with a widening hair part.

Some density loss at the hairline – making it difficult to differentiate this hair loss type from the early stages of androgenic alopecia (AGA).

Diffuse thinning across the entire scalp, often most notable at the hairline and/or via a widening hair part. At this stage, hair loss is often only noticeable to the individual and is not always cosmetically perceptible.

Example: early-stage diffuse lichen planopilarus. Scalp pain, discomfort, and redness may persist alongside ncreased hair shedding. Hair loss may present diffusely, in clustered patches, and/or even as hairline recession. In its earliest of stages, without a scalp biopsy or trichoscopic evaluation, scarring alopecias can be difficult to distinguish from androgenic alopecia (AGA).

Example: early-stage frontal fibrosing alopecia. Some scalp pain, discomfort, and redness alongside increased hair shedding, with slight recession that is uniformly distributed across the entire frontal band of the hairline. There may be a strong demarcated line of “hair” and “no hair” where the hairline starts – with the disappearance of vellus hairs that might otherwise constitute a more “natural look to the hairline. In its earliest of stages, without a scalp biopsy or trichoscopic evaluation, scarring alopecias can be difficult to distinguish from female pattern hair loss.

One or multiple small patches of hair loss may occur on the scalp – often with irregular patterns and clear demarcated zones of “hair” and “no hair”.

One or multiple small patches of hair loss may occur on the scalp – often with irregular patterns and clear demarcated zones of “hair” and “no hair”.

Healthy sebaceous gland, with no evidence of enlargement or destruction.

Healthy hair diameter, with no signs of miniaturization relative to other hair follicles.

Arrector pili muscle is anchored to all hair follicles within the hair follicle cluster. The stem cell bulge shows no evidence of deterioration.

No erosion of subcutaneous fat beneath the hair follicle cluster. Healthy levels of microvasculature support to the hair follicles, with no evidence of degeneration.

Sebaceous gland may slightly enlarge relative to the size of the hair follicle.

A slight decrease in hair strand thickness relative to the previous hair cycle.

Slight losses to both subcutaneous fat and microvasculature support to the hair follicle.

Lymphocytic infiltrates (i.e., inflammation) often present at the level of the infundibulum.

Increased levels of dihydrotestosterone (DHT) near the hair follicle root sheath and dermal papillae cell cluster.

Increased microorganism activity (i.e., p. acnes and/or malassezia) near the epidermis and sebaceous gland.

Aside from a 10-20% increase in telogen hairs, scalp biopsies of early-stage telogen effluvium tend to show little histological differences from healthy hair follicles.

Some destruction of the sebaceous gland, and its replacement with fibrosis (i.e., scar tissue).

Lymphocytic and neutrophilic infiltrate (i.e., inflammation) at the level of the ostia and infundibulum – with some inflammation extending lower into the peribulbar region.

Reddened skin denotes more widespread inflammation beyond just the hair follicle. In scarring alopecias, inflammation tends to be much more insidious versus androgenic alopecia, telogen effluvium, and alopecia areata.

Fibrosis (i.e., scarring) surrounding the hair follicle. In scarring alopecias, fibrosis tends to onset faster and is more widespread versus androgenic alopecia.

Damage to the hair follicle stem cell bulge. This is another differentiating characteristic of scarring alopecias from androgenic alopecia, as hair follicles affected by androgenic alopecia tend to retain their hair follicle stem cells – even in advanced stages.

Peri- and intra-bulbar lymphocytic infiltrate (i.e., inflammation) concentrated at the base of the hair follicle, which diminishes as it extends upward toward the infundibulum.

Hair thickness changes within the same hair cycle: miniaturization at the base of the hair strand that occurs during active growth, suggesting miniaturization that is not dependent on hair cycling. This is a key differentiator from androgenic alopecia.

Hairline recession progresses backward. Hair diameter diversity is greater than 20% and hair follicle clusters now produce 1-2 terminal hairs.

Diffuse thinning, the appearance of a wider hair part, and/or potential increased hair loss at the crown.

Diffuse thinning progresses, with some loss of the center hairline. Hair diameter diversity is greater than 20% and hair follicle clusters now produce 1-2 terminal hairs.

Hair part continues to widen, with anagen:telogen ratios continuing to decrease.

Global hair density continues to decrease, presenting with further widening to the hair part.

Global diffuse thinning may be indistinguishable from androgenic alopecia (AGA) and/or diffuse unpatterned alopecia (DUPA) – at least without dermascopic assessment for hair diameter diversity.

Global hair density continues to decrease, presenting with further widening to the hair part. Without trichoscopic examination for hair diameter diversity, this stage of telogen effluvium often mirrors that of female pattern hair loss.

Example: middle-stage diffuse lichen planopilarus. Scalp pain, discomfort, and redness may continue alongside increased hair shedding – with hair loss continue to advance diffusely, in clustered patches, and/or as recession of the hairline.

Some hair loss may appear unevenly distributed relative to other scalp regions. Skin may appear inflamed.

Example: middle-stage frontal fibrosing alopecia. Scalp pain, discomfort, and redness may persist alongside increased hair shedding. Hair loss may present as moderate-to-significant hairline recession that is uniformly distributed across the entire frontal band of the hairline. The demarcated line of “hair” and “no hair” where the hairline starts continues to march backwards – with the disappearance of vellus hairs that often constitute a more “natural look to the hairline.

The frontal band of uniform hair loss may also begin to impact hair above the parietal plates and toward the sideburns.

Patches of hair loss may expand and converge into larger, irregularly-shaped zones of loss.

New patches of hair loss may emerge and begin to span larger portions of the scalp.

Irregular patches of hair loss may expand to cover larger areas of the scalp.

New patches of hair loss may emerge – furthering the loss of hair across the scalp.

A marked decrease in hair strand thickness relative to the previous hair cycle.

Perifollicular fibrosis (i.e., scar tissue) begins to onset surrounding the hair follicle.

Sebaceous glands continue to enlarge.

Further erosion of subcutaneous fat and microvasculature degradation, thereby increasing the distance between the hypodermic and the dermal papilla.

As lymphocytic infiltrate decreases, it is replaced by perifollicular fibrosis (i.e., scar tissue).

Aside from a 20-40% increase in telogen hairs, scalp biopsies of moderate telogen effluvium tend to show little histological differences from healthy hair follicles.

Near-complete destruction of the sebaceous gland and its replacement with fibrosis (i.e., scarring).

Degradation of the arrector pili.

Significant deterioration of the hair follicle stem cell bulge.

Decreased hair thickness and some hair follicle miniaturization relative to the previous hair cycle. With just this characteristic alone, scarring alopecias are difficult to distinguish from androgenic alopecia.

Erosion of subcutaneous fat.

Follicular streamers act as remnants for the depth at which the hair follicle resided in previous hair cycles.

Peri- and intra-bulbar lymphocytic infiltrates (i.e., inflammation) persist surrounding the hair follicles, and are now accompanied by the dysregulation of melanin (i.e., pigment-producing cells).

Sebaceous glands remain intact – with their sizes unchanged. This is a distinguishing characteristic from androgenic alopecia (where sebaceous glands often enlarge) and scarring alopecias (where sebaceous glands are destroyed).

Near-complete loss of visible hair in scalp regions above the galea aponeurotica. Hair follicle clusters now produce 1-2 vellus hairs.

Near-complete loss of hair density across most scalp regions. Remaining hair strands are significantly miniaturized, and most hair follicle clusters now produce 1-2 vellus and/or terminal hairs.

Global diffuse thinning leads to significant reductions in overall hair density, and a wide hair part resemblant of the late stages of female pattern hair loss.

Thinning on the sides and back of the scalp also pronounced.

Global diffuse thinning leads to significant reductions in overall hair density, and a wide hair part resemblant of the late stages of female pattern hair loss.

Example: advanced diffuse lichen planopilarus. Scalp pain, discomfort, and redness alongside hair shedding may have subsided. Hair loss has advanced diffusely, in clustered patches, and/or as recession of the hairline – though in later stages, irregularly-patterned hair loss becomes more likely.

Tufts of hair may present sporadically and at the hairline, surrounded by skin that may appear reddened and/or fibrotic (i.e., scarred)

At lichen planopilarus advances, some irregularity in the diffusion of hair loss becomes more likely – with the potential for some slick-bald patches of loss.

Example: advanced frontal fibrosing alopecia. Scalp pain, discomfort, and redness alongside hair shedding may have subsided. The inform “marching backward” of the hairline continues – often with a strongly demarcated zone of “hair” and “no hair” where the hairline starts.

No evidence of terminal or vellus hairs where the hairline originally resided.

No loss of hair in areas outside of the hairline “band”.

Loss of the hairline band may progress backward along the parietal plate, leading to complete hair loss on the scalp sides and/or sideburns.

In some cases, frontal fibrosing alopecia may spread to the eyebrows, leading to hair density loss in these regions.

In alopecia universalis / alopecia totalis, there is often complete loss of hair across the entire scalp and face.

Eyebrows and eyelashes are also often affected.

Beard growth is also often affected.

In alopecia universalis / alopecia totalis, there is often complete loss of hair across the entire scalp and face.

Eyebrows and eyelashes are also often affected.

Detachment of the arrector pili muscle from both the hair follicle stem cell bulge and hair follicle cluster – a marker suggesting difficulty in reversibility of hair follicle miniaturization even with current treatments.

Affected hair strands only capable of growing 1-3 centimeters from the scalp before entering categen.

Hair strand thickness markedly decreased, often alongside a loss of hair pigment. This denotes the presence of a vellus hair.

Increased perifollicular fibrosis (i.e., scar tissue) entrapping the hair follicle cluster.

Further erosion of adipose tissue and degradation of microvascular support to remaining hair follicles – accounting for a 2.6-fold decrease in subcutaneous blood flow in balding regions and a 40% reduction in transcutaneous oxygen levels.

Lymphocytic infiltrate is further reduced, with more of the inflammation resolving to perifollicular fibrosis (i.e., scar tissue).

Aside from a 40%+ increase in telogen hairs, scalp biopsies of advanced telogen effluvium tend to show little histological differences from healthy hair follicles.

Complete destruction of the hair follicle and hair strand.

Sebaceous gland is completely absent and fully replaced with fibrosis (i.e., scar tissue).

Remnants of the arrector pili, ensnared in fibrosis (i.e., scar tissue) and completely detached from the hair follicle stem cell bulge and hair follicle.

Significant erosion of subcutaneous fat and microvasculature support in the area where a hair follicle once resided.

Widespread fibrosis extending beyond the region of the previously-existing hair follicle.

As the hair follicle moves further up the dermis, follicular streamers collect underneath where they represent debris from and the depth of previous hair cycles.

The stem cell bulge and arrector pili muscles remain attached to the hair follicle cluster. This is a distinguishing factor from androgenic alopecia (where detachment of the arrector pili can occur) and scarring alopecias (where destruction of both the arrector pili and hair follicle stem cell bulge can occur).

In some cases of long-standing and/or chronic alopecia areata, sebaceous glands may shrink or appear absent. But unlike scarring alopecias, these sebaceous glands are not shrouded in fibrosis (i.e., scar tissue).

Hair follicles no longer remain in anagen for long enough to grow out of the epidermis and produce cosmetically visible hair.

Key Takeaways

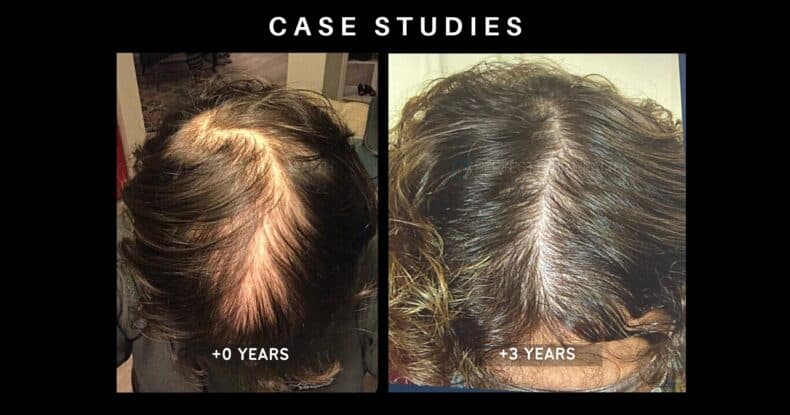

Correctly identifying your hair loss is critical. If you don’t get your diagnosis right, you won’t know the causes of your hair loss, and you’ll delay your access to the right treatments. For examples of this, see our case studies:

Alessandro

Who’s finally seeing hair regrowth after 10+ years of failed treatments

Carlo

Who’s achieving hair gains even with a scarring alopecia (previously thought to be impossible)

For now, here’s what you should know:

- It’s critical to identify your hair loss type(s). This determines your hair loss causes & treatments.

- Misdiagnoses of telogen effluvium & androgenic alopecia are common.

- Hair loss presentations may assist with diagnoses, but can also be misleading (see Carlo & Alessandro’s videos).

- The best person to assist with a diagnosis is a dermatologist who specializes in hair loss disorders.

- Use our support channels & the resources on this page to get closer to a real diagnosis!

Get Supported

Our team can help you identify your hair loss type(s):

Androgenic Alopecia

Presentations

Get a close-up view of how androgenic alopecia advances – in men and women – at both a cosmetic and microscopic level.

Causes & Treatments

Here’s a summary of the known causes and potential treatments for Androgenic Alopecia.

How to Diagnose

Use our resources to help you identify (or rule out) Androgenic Alopecia.

Juvenile hairline with no evidence of recession or diffuse thinning. All scalp regions show less than 20% hair diameter diversity (i.e., hair follicle miniaturization) – with hair follicle clusters producing 2-5 hairs per cluster.

Full hair density, with no evidence of hairline recession or diffuse thinning. All scalp regions show less than 20% hair diameter diversity (i.e., hair follicle miniaturization) – with hair follicle clusters producing 2-5 hairs per cluster.

Slight hairline recession beginning at the temples. Hair diameter diversity is greater than 20% and hair follicle clusters now produce 1-3 terminal hairs.

A decrease in hair density and anagen:telogen ratios may already present across the scalp, even without cosmetic levels of hair loss.

Slight diffuse hair loss across the scalp, often represented through a “widened” hair part. Hair diameter diversity is greater than 20% and hair follicle clusters now produce 1-3 terminal hairs.

Hairline recession progresses backward. Hair diameter diversity is greater than 20% and hair follicle clusters now produce 1-2 terminal hairs.

Diffuse thinning, the appearance of a wider hair part, and/or potential increased hair loss at the crown.

Diffuse thinning progresses, with some loss of the center hairline. Hair diameter diversity is greater than 20% and hair follicle clusters now produce 1-2 terminal hairs.

Hair part continues to widen, with anagen:telogen ratios continuing to decrease.

Near-complete loss of visible hair in scalp regions above the galea aponeurotica. Hair follicle clusters now produce 1-2 vellus hairs.

Near-complete loss of hair density across most scalp regions. Remaining hair strands are significantly miniaturized, and most hair follicle clusters now produce 1-2 vellus and/or terminal hairs.

Healthy sebaceous gland, with no evidence of enlargement or destruction.

Healthy hair diameter, with no signs of miniaturization relative to other hair follicles.

Arrector pili muscle is anchored to all hair follicles within the hair follicle cluster. The stem cell bulge shows no evidence of deterioration.

No erosion of subcutaneous fat beneath the hair follicle cluster. Healthy levels of microvasculature support to the hair follicles, with no evidence of degeneration.

Sebaceous gland may slightly enlarge relative to the size of the hair follicle.

A slight decrease in hair strand thickness relative to the previous hair cycle.

Slight losses to both subcutaneous fat and microvasculature support to the hair follicle.

Lymphocytic infiltrates (i.e., inflammation) often present at the level of the infundibulum.

Increased levels of dihydrotestosterone (DHT) near the hair follicle root sheath and dermal papillae cell cluster.

Increased microorganism activity (i.e., p. acnes and/or malassezia) near the epidermis and sebaceous gland.

A marked decrease in hair strand thickness relative to the previous hair cycle.

Perifollicular fibrosis (i.e., scar tissue) begins to onset surrounding the hair follicle.

Sebaceous glands continue to enlarge.

Further erosion of subcutaneous fat and microvasculature degradation, thereby increasing the distance between the hypodermic and the dermal papilla.

As lymphocytic infiltrate decreases, it is replaced by perifollicular fibrosis (i.e., scar tissue).

Detachment of the arrector pili muscle from both the hair follicle stem cell bulge and hair follicle cluster – a marker suggesting difficulty in reversibility of hair follicle miniaturization even with current treatments.

Affected hair strands only capable of growing 1-3 centimeters from the scalp before entering categen.

Hair strand thickness markedly decreased, often alongside a loss of hair pigment. This denotes the presence of a vellus hair.

Increased perifollicular fibrosis (i.e., scar tissue) entrapping the hair follicle cluster.

Further erosion of adipose tissue and degradation of microvascular support to remaining hair follicles – accounting for a 2.6-fold decrease in subcutaneous blood flow in balding regions and a 40% reduction in transcutaneous oxygen levels.

Lymphocytic infiltrate is further reduced, with more of the inflammation resolving to perifollicular fibrosis (i.e., scar tissue).

Causes & Treatments

Here’s a summary of the known causes and potential treatments for Androgenic Alopecia.

| Causes | Targets | ||

| Primary | Secondary | Primary | Secondary |

|

|

|||

How to Diagnose

Use our resources to help you identify (or rule out) Androgenic Alopecia.

Telogen Effluvium

Presentations

Get a close-up view of telogen effluvium – in men and women – at both a cosmetic and microscopic level.

Causes & Treatments

Here’s a summary of the known causes and potential treatments for Telogen Effluvium.

How to Diagnose

Use our resources to help you identify (or rule out) Telogen Effluvium.

Juvenile hairline with no evidence of recession or diffuse thinning. All scalp regions show less than 20% hair diameter diversity (i.e., hair follicle miniaturization) – with hair follicle clusters producing 2-5 hairs per cluster.

Full hair density, with no evidence of hairline recession or diffuse thinning. All scalp regions show less than 20% hair diameter diversity (i.e., hair follicle miniaturization) – with hair follicle clusters producing 2-5 hairs per cluster.

Diffuse thinning across the entire scalp, often most notable with a widening hair part.

Some density loss at the hairline – making it difficult to differentiate this hair loss type from the early stages of androgenic alopecia (AGA).

Diffuse thinning across the entire scalp, often most notable at the hairline and/or via a widening hair part. At this stage, hair loss is often only noticeable to the individual and is not always cosmetically perceptible.

Global hair density continues to decrease, presenting with further widening to the hair part.

Global diffuse thinning may be indistinguishable from androgenic alopecia (AGA) and/or diffuse unpatterned alopecia (DUPA) – at least without dermascopic assessment for hair diameter diversity.

Global hair density continues to decrease, presenting with further widening to the hair part. Without trichoscopic examination for hair diameter diversity, this stage of telogen effluvium often mirrors that of female pattern hair loss.

Global diffuse thinning leads to significant reductions in overall hair density, and a wide hair part resemblant of the late stages of female pattern hair loss.

Thinning on the sides and back of the scalp also pronounced.

Global diffuse thinning leads to significant reductions in overall hair density, and a wide hair part resemblant of the late stages of female pattern hair loss.

Healthy sebaceous gland, with no evidence of enlargement or destruction.

Healthy hair diameter, with no signs of miniaturization relative to other hair follicles.

Arrector pili muscle is anchored to all hair follicles within the hair follicle cluster. The stem cell bulge shows no evidence of deterioration.

No erosion of subcutaneous fat beneath the hair follicle cluster. Healthy levels of microvasculature support to the hair follicles, with no evidence of degeneration.

Aside from a 10-20% increase in telogen hairs, scalp biopsies of early-stage telogen effluvium tend to show little histological differences from healthy hair follicles.

Aside from a 20-40% increase in telogen hairs, scalp biopsies of moderate telogen effluvium tend to show little histological differences from healthy hair follicles.

Aside from a 40%+ increase in telogen hairs, scalp biopsies of advanced telogen effluvium tend to show little histological differences from healthy hair follicles.

Causes & Treatments

Here’s a summary of the known causes and potential treatments for Telogen Effluvium.

| Causes | Targets | ||

| Acute | Chronic | Acute | Chronic |

|

|||

How to Diagnose

Use our resources to help you identify (or rule out) Telogen Effluvium.

Scarring Alopecia

Presentations

Get a close-up view of how scarring alopecia advances – in men and women – at both a cosmetic and microscopic level.

Causes & Treatments

Here’s a summary of the known causes and potential treatments for Scarring Alopecia.

How to Diagnose

Use our resources to help you identify (or rule out) Scarring Alopecia.

Juvenile hairline with no evidence of recession or diffuse thinning. All scalp regions show less than 20% hair diameter diversity (i.e., hair follicle miniaturization) – with hair follicle clusters producing 2-5 hairs per cluster.

Full hair density, with no evidence of hairline recession or diffuse thinning. All scalp regions show less than 20% hair diameter diversity (i.e., hair follicle miniaturization) – with hair follicle clusters producing 2-5 hairs per cluster.

Example: early-stage diffuse lichen planopilarus. Scalp pain, discomfort, and redness may persist alongside ncreased hair shedding. Hair loss may present diffusely, in clustered patches, and/or even as hairline recession. In its earliest of stages, without a scalp biopsy or trichoscopic evaluation, scarring alopecias can be difficult to distinguish from androgenic alopecia (AGA).

Example: early-stage frontal fibrosing alopecia. Some scalp pain, discomfort, and redness alongside increased hair shedding, with slight recession that is uniformly distributed across the entire frontal band of the hairline. There may be a strong demarcated line of “hair” and “no hair” where the hairline starts – with the disappearance of vellus hairs that might otherwise constitute a more “natural look to the hairline. In its earliest of stages, without a scalp biopsy or trichoscopic evaluation, scarring alopecias can be difficult to distinguish from female pattern hair loss.

Example: middle-stage diffuse lichen planopilarus. Scalp pain, discomfort, and redness may continue alongside increased hair shedding – with hair loss continue to advance diffusely, in clustered patches, and/or as recession of the hairline.

Some hair loss may appear unevenly distributed relative to other scalp regions. Skin may appear inflamed.

Example: middle-stage frontal fibrosing alopecia. Scalp pain, discomfort, and redness may persist alongside increased hair shedding. Hair loss may present as moderate-to-significant hairline recession that is uniformly distributed across the entire frontal band of the hairline. The demarcated line of “hair” and “no hair” where the hairline starts continues to march backwards – with the disappearance of vellus hairs that often constitute a more “natural look to the hairline.

The frontal band of uniform hair loss may also begin to impact hair above the parietal plates and toward the sideburns.

Example: advanced diffuse lichen planopilarus. Scalp pain, discomfort, and redness alongside hair shedding may have subsided. Hair loss has advanced diffusely, in clustered patches, and/or as recession of the hairline – though in later stages, irregularly-patterned hair loss becomes more likely.

Tufts of hair may present sporadically and at the hairline, surrounded by skin that may appear reddened and/or fibrotic (i.e., scarred)

At lichen planopilarus advances, some irregularity in the diffusion of hair loss becomes more likely – with the potential for some slick-bald patches of loss.

Example: advanced frontal fibrosing alopecia. Scalp pain, discomfort, and redness alongside hair shedding may have subsided. The inform “marching backward” of the hairline continues – often with a strongly demarcated zone of “hair” and “no hair” where the hairline starts.

No evidence of terminal or vellus hairs where the hairline originally resided.

No loss of hair in areas outside of the hairline “band”.

Loss of the hairline band may progress backward along the parietal plate, leading to complete hair loss on the scalp sides and/or sideburns.

In some cases, frontal fibrosing alopecia may spread to the eyebrows, leading to hair density loss in these regions.

Healthy sebaceous gland, with no evidence of enlargement or destruction.

Healthy hair diameter, with no signs of miniaturization relative to other hair follicles.

Arrector pili muscle is anchored to all hair follicles within the hair follicle cluster. The stem cell bulge shows no evidence of deterioration.

No erosion of subcutaneous fat beneath the hair follicle cluster. Healthy levels of microvasculature support to the hair follicles, with no evidence of degeneration.

Some destruction of the sebaceous gland, and its replacement with fibrosis (i.e., scar tissue).

Lymphocytic and neutrophilic infiltrate (i.e., inflammation) at the level of the ostia and infundibulum – with some inflammation extending lower into the peribulbar region.

Reddened skin denotes more widespread inflammation beyond just the hair follicle. In scarring alopecias, inflammation tends to be much more insidious versus androgenic alopecia, telogen effluvium, and alopecia areata.

Fibrosis (i.e., scarring) surrounding the hair follicle. In scarring alopecias, fibrosis tends to onset faster and is more widespread versus androgenic alopecia.

Damage to the hair follicle stem cell bulge. This is another differentiating characteristic of scarring alopecias from androgenic alopecia, as hair follicles affected by androgenic alopecia tend to retain their hair follicle stem cells – even in advanced stages.

Near-complete destruction of the sebaceous gland and its replacement with fibrosis (i.e., scarring).

Degradation of the arrector pili.

Significant deterioration of the hair follicle stem cell bulge.

Decreased hair thickness and some hair follicle miniaturization relative to the previous hair cycle. With just this characteristic alone, scarring alopecias are difficult to distinguish from androgenic alopecia.

Erosion of subcutaneous fat.

Complete destruction of the hair follicle and hair strand.

Sebaceous gland is completely absent and fully replaced with fibrosis (i.e., scar tissue).

Remnants of the arrector pili, ensnared in fibrosis (i.e., scar tissue) and completely detached from the hair follicle stem cell bulge and hair follicle.

Significant erosion of subcutaneous fat and microvasculature support in the area where a hair follicle once resided.

Widespread fibrosis extending beyond the region of the previously-existing hair follicle.

Causes & Treatments

Here’s a summary of the known causes and potential treatments for Scarring Alopecia.

| Causes | Targets | ||

| Primary | Secondary | Primary | Secondary |

|

|

|

|

How to Diagnose

Use our resources to help you identify (or rule out) Scarring Alopecia.

Alopecia Areata

Presentations

Get a close-up view of how Alopecia Areata advances – in men and women – at both a cosmetic and microscopic level.

Causes & Treatments

Here’s a summary of the known causes and potential treatments for Alopecia Areata.

How to Diagnose

Use our resources to help you identify (or rule out) Alopecia Areata.

Juvenile hairline with no evidence of recession or diffuse thinning. All scalp regions show less than 20% hair diameter diversity (i.e., hair follicle miniaturization) – with hair follicle clusters producing 2-5 hairs per cluster.

Full hair density, with no evidence of hairline recession or diffuse thinning. All scalp regions show less than 20% hair diameter diversity (i.e., hair follicle miniaturization) – with hair follicle clusters producing 2-5 hairs per cluster.

One or multiple small patches of hair loss may occur on the scalp – often with irregular patterns and clear demarcated zones of “hair” and “no hair”.

One or multiple small patches of hair loss may occur on the scalp – often with irregular patterns and clear demarcated zones of “hair” and “no hair”.

Patches of hair loss may expand and converge into larger, irregularly-shaped zones of loss.

New patches of hair loss may emerge and begin to span larger portions of the scalp.

Irregular patches of hair loss may expand to cover larger areas of the scalp.

New patches of hair loss may emerge – furthering the loss of hair across the scalp.

In alopecia universalis / alopecia totalis, there is often complete loss of hair across the entire scalp and face.

Eyebrows and eyelashes are also often affected.

Beard growth is also often affected.

In alopecia universalis / alopecia totalis, there is often complete loss of hair across the entire scalp and face.

Eyebrows and eyelashes are also often affected.

Healthy sebaceous gland, with no evidence of enlargement or destruction.

Healthy hair diameter, with no signs of miniaturization relative to other hair follicles.

Arrector pili muscle is anchored to all hair follicles within the hair follicle cluster. The stem cell bulge shows no evidence of deterioration.

No erosion of subcutaneous fat beneath the hair follicle cluster. Healthy levels of microvasculature support to the hair follicles, with no evidence of degeneration.

Peri- and intra-bulbar lymphocytic infiltrate (i.e., inflammation) concentrated at the base of the hair follicle, which diminishes as it extends upward toward the infundibulum.

Hair thickness changes within the same hair cycle: miniaturization at the base of the hair strand that occurs during active growth, suggesting miniaturization that is not dependent on hair cycling. This is a key differentiator from androgenic alopecia.

Follicular streamers act as remnants for the depth at which the hair follicle resided in previous hair cycles.

Peri- and intra-bulbar lymphocytic infiltrates (i.e., inflammation) persist surrounding the hair follicles, and are now accompanied by the dysregulation of melanin (i.e., pigment-producing cells).

Sebaceous glands remain intact – with their sizes unchanged. This is a distinguishing characteristic from androgenic alopecia (where sebaceous glands often enlarge) and scarring alopecias (where sebaceous glands are destroyed).

As the hair follicle moves further up the dermis, follicular streamers collect underneath where they represent debris from and the depth of previous hair cycles.

The stem cell bulge and arrector pili muscles remain attached to the hair follicle cluster. This is a distinguishing factor from androgenic alopecia (where detachment of the arrector pili can occur) and scarring alopecias (where destruction of both the arrector pili and hair follicle stem cell bulge can occur).

In some cases of long-standing and/or chronic alopecia areata, sebaceous glands may shrink or appear absent. But unlike scarring alopecias, these sebaceous glands are not shrouded in fibrosis (i.e., scar tissue).

Hair follicles no longer remain in anagen for long enough to grow out of the epidermis and produce cosmetically visible hair.

Causes & Treatments

Here’s a summary of the known causes and potential treatments for Alopecia Areata.

| Causes | Targets | ||

| Primary | Secondary | Primary | Secondary |

|

|

|

|

How to Diagnose

Use our resources to help you identify (or rule out) Alopecia Areata.

Scroll Down

Scroll Down