- About

- Mission Statement

Education. Evidence. Regrowth.

- Education.

Prioritize knowledge. Make better choices.

- Evidence.

Sort good studies from the bad.

- Regrowth.

Get bigger hair gains.

Team MembersPhD's, resarchers, & consumer advocates.

- Rob English

Founder, researcher, & consumer advocate

- Research Team

Our team of PhD’s, researchers, & more

Editorial PolicyDiscover how we conduct our research.

ContactHave questions? Contact us.

Before-Afters- Transformation Photos

Our library of before-after photos.

- — Jenna, 31, U.S.A.

I have attached my before and afters of my progress since joining this group...

- — Tom, 30, U.K.

I’m convinced I’ve recovered to probably the hairline I had 3 years ago. Super stoked…

- — Rabih, 30’s, U.S.A.

My friends actually told me, “Your hairline improved. Your hair looks thicker...

- — RDB, 35, New York, U.S.A.

I also feel my hair has a different texture to it now…

- — Aayush, 20’s, Boston, MA

Firstly thank you for your work in this field. I am immensely grateful that...

- — Ben M., U.S.A

I just wanted to thank you for all your research, for introducing me to this method...

- — Raul, 50, Spain

To be honest I am having fun with all this and I still don’t know how much...

- — Lisa, 52, U.S.

I see a massive amount of regrowth that is all less than about 8 cm long...

Client Testimonials150+ member experiences.

Scroll DownPopular Treatments

Scroll DownPopular Treatments- Treatments

Popular treatments. But do they work?

- Finasteride

- Oral

- Topical

- Dutasteride

- Oral

- Topical

- Mesotherapy

- Minoxidil

- Oral

- Topical

- Ketoconazole

- Shampoo

- Topical

- Low-Level Laser Therapy

- Therapy

- Microneedling

- Therapy

- Platelet-Rich Plasma Therapy (PRP)

- Therapy

- Scalp Massages

- Therapy

More

IngredientsTop-selling ingredients, quantified.

- Saw Palmetto

- Redensyl

- Melatonin

- Caffeine

- Biotin

- Rosemary Oil

- Lilac Stem Cells

- Hydrolyzed Wheat Protein

- Sodium Lauryl Sulfate

More

ProductsThe truth about hair loss "best sellers".

- Minoxidil Tablets

Xyon Health

- Finasteride

Strut Health

- Hair Growth Supplements

Happy Head

- REVITA Tablets for Hair Growth Support

DS Laboratories

- FoliGROWTH Ultimate Hair Neutraceutical

Advanced Trichology

- Enhance Hair Density Serum

Fully Vital

- Topical Finasteride and Minoxidil

Xyon Health

- HairOmega Foaming Hair Growth Serum

DrFormulas

- Bio-Cleansing Shampoo

Revivogen MD

more

Key MetricsStandardized rubrics to evaluate all treatments.

- Evidence Quality

Is this treatment well studied?

- Regrowth Potential

How much regrowth can you expect?

- Long-Term Viability

Is this treatment safe & sustainable?

Free Research- Free Resources

Apps, tools, guides, freebies, & more.

- Topical Finasteride Calculator

- Interactive Guide: What Causes Hair Loss?

- Free Guide: Standardized Scalp Massages

- 7-Day Hair Loss Email Course

- Ingredients Database

- Interactive Guide: Hair Loss Disorders

- Treatment Guides

- Product Lab Tests: Purity & Potency

- Evidence Quality Masterclass

More

Articles100+ free articles.

-

Cannabidiol (CBD) Increases Hair Counts By 246%? Not So Fast.

-

Creatine: Does It Worsen Hair Loss? It Depends On The Hair Loss Type.

-

Can Progesterone Improve Hair Regrowth?

-

CRABP2: Can This Gene Predict Regrowth From Retinoids?

-

BTD: Can This Gene Predict Regrowth From Biotin?

-

COL1A1: Can This Gene Predict Regrowth From Collagen Support?

-

2dDR For Hair Loss: What Do We Know So Far About This Sugar?

-

CYP19A1: Can This Gene Predict Regrowth From Hormone Therapy?

PublicationsOur team’s peer-reviewed studies.

- Microneedling and Its Use in Hair Loss Disorders: A Systematic Review

- Use of Botulinum Toxin for Androgenic Alopecia: A Systematic Review

- Conflicting Reports Regarding the Histopathological Features of Androgenic Alopecia

- Self-Assessments of Standardized Scalp Massages for Androgenic Alopecia: Survey Results

- A Hypothetical Pathogenesis Model For Androgenic Alopecia:Clarifying The Dihydrotestosterone Paradox And Rate-Limiting Recovery Factors

Menu- AboutAbout

- Mission Statement

Education. Evidence. Regrowth.

- Team Members

PhD's, resarchers, & consumer advocates.

- Editorial Policy

Discover how we conduct our research.

- Contact

Have questions? Contact us.

- Before-Afters

ArticlesHow Long Does a Hair Transplant Last?

First Published Mar 5 2022Last Updated Oct 29 2024MiscellaneousNatural Remedies Researched & Written By:Perfect Hair Health Team

Researched & Written By:Perfect Hair Health Team Reviewed By:Rob English, Medical Editor

Reviewed By:Rob English, Medical Editor

Want help with your hair regrowth journey?

Get personalized support, product recommendations, video calls, and more from our researchers, trichologists, and PhD's dedicated to getting you the best possible outcomes.

Learn MoreArticle Summary

Fifty years ago, studies on hair transplants indicated that transplanted hairs never thin. But a 2020 study now suggests that hair transplants can thin… and even just four years post-surgery. What could explain these conflicting results, and what can we make of the new data? This article uncovers the answers, and presents evidence suggesting that these new results might actually a reflect a change in hair transplant techniques over time – such as reductions to punch graft sizings.

Full Article

How long does a hair transplant last? The answers are debated.

Nearly all the top-ranking articles on google claim that hair transplants are permanent. At first glance, this makes sense. After all, early hair transplant studies from the 1960s and 1970s found hairs transplanted to balding regions survive the duration of those studies.[1]https://nyaspubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1749-6632.1960.tb40920.x And one editorial argued that, over a 15-year period, there has been no instance of transplanted hairs thinning (so long as the donor area also remains intact).[2]https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamaotolaryngology/article-abstract/603301

Yet new data suggest hair transplants can thin. And sometimes, within just a few years after the procedure.

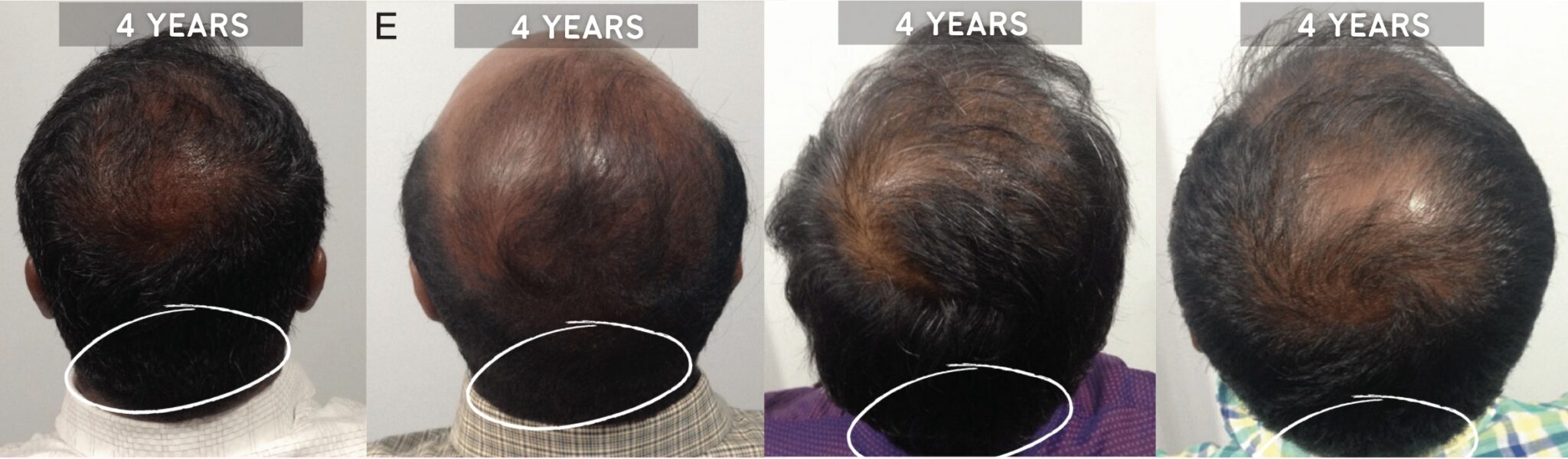

In a 2020 study on the long-term viability of today’s transplants, just four years after the procedure, over 90% of patients experienced visible hair thinning of transplanted hairs.[3]https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33911409/

So what’s the truth? Are early studies telling the whole story about hair transplants? Are there problems with the 2020 study? Do hair transplants actually thin? And if so, what does this tell us about two competing theories: donor dominance versus recipient site influence?

We’ll uncover the answers (and our take on the data) in this article. Specifically, we’ll discuss:

- The truth about hair transplants

- Two competing theories: donor dominance and recipient site influence

- The truth about today’s hair transplants

- Why early research doesn’t seem to fit today’s reality

Finally, we’ll answer that all-important question: are hair transplants worth it?

About Hair Transplants

Hair transplants are a surgical treatment for androgenic alopecia, also called pattern hair loss. This hair loss disorder is driven by genetics, hormones, and other factors. Without treatment, it typically worsens.

During a hair transplant, a surgeon takes hair from a donor site (typically at the back of the head) and places it where needed.

In the early days, transplants typically looked very obvious. See this example.

Early days of hair transplants (plugs)

Nowadays, many hair transplants are nearly imperceptible. Surgeons have made incredible progress reshaping hairlines, improving density, and filling in bald spots. Just look at the work from Hasson and Wong – two esteemed transplant surgeons.

Modern-day hair transplant quality

As such, it’s no wonder the hair transplant industry has exploded worldwide. It’s commonplace for people to travel to Turkey, get a low-cost transplant, and be seen bandaged up in the airport boarding their flight home the next day.

Many hair transplants clinics, including those in the US, guarantee permanent results. But do these promises align with the clinical data? In the early days of hair transplant research, the answer was, “Yes.” Today, new research is telling a different story – one suggestive that hair transplants, contrary to popular belief, can start to thin.

To understand the discrepancy (and get to the truth), we need to revisit the scientific history of hair transplants and the pioneering work of a doctor named Norman Orentreich. Then, we need to see how his research stacks up to new science.

Hair Transplant Studies (1950’s to 1970’s)

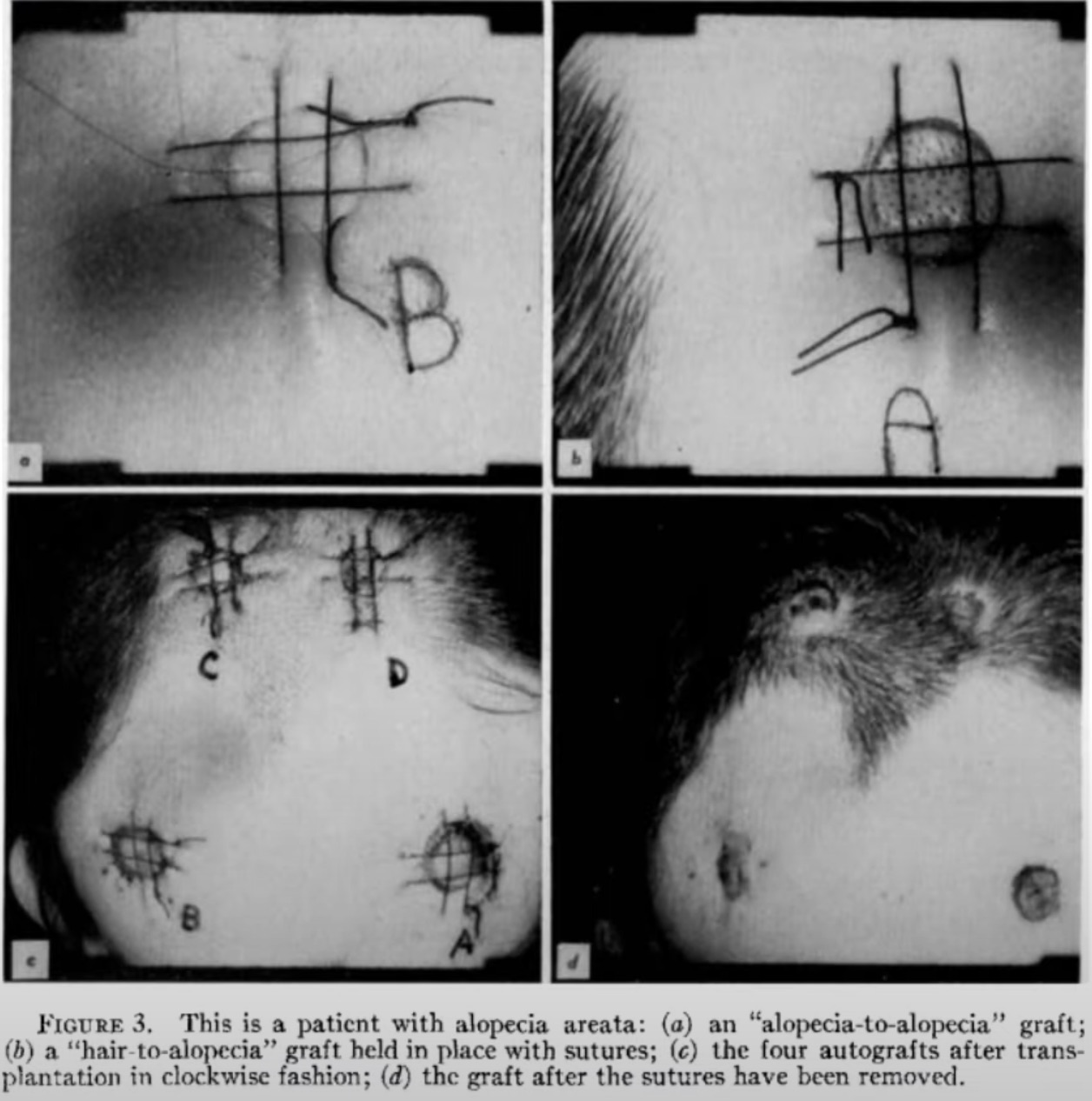

In 1959, a doctor named Norman Orentreich published the first ever transplant study on men with androgenic alopecia.[4]https://nyaspubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1749-6632.1960.tb40920.x

Norman Orentreich wanted to understand if our scalp environments had anything to do with the onset of this hair loss disorder. At the time, researchers suspected that pattern hair loss might be related to scalp tension, the contraction of muscles surrounding the scalp perimeter, and even microvascular insufficiencies in certain scalp regions versus others.

To understand if there was any merit to these ideas, Orentreich ran the following experiment.

Using over 50 subjects, Orentreich took punch grafts from the backs of men’s scalps, where hair is generally protected from baldness. He then moved those grafts to the hairlines where the men’s hair was receding.

The goal: to find out how these transplanted hairs behaved over time.

- Would balding hairs transplanted into healthy areas remain bald? Or would they regrow in their new area?

- Would healthy hairs transplanted into balding areas remain healthy? Or would they start miniaturizing when moved to regions of baldness?

Orentreich performed the surgeries to find out. Then he got busy waiting.

Two and a half years later, Orentreich discovered something fascinating:

- Healthy hairs taken from the back of the head and moved to the hairline continued to grow just fine, despite the men’s hairlines continuing to recede.

- Bald skin transplanted to healthy regions remained bald, despite being placed in hair-bearing regions of the scalp.

Orentreich described this phenomenon as donor dominance, meaning the transplanted hairs retained their original growth characteristics, despite being placed in a new environment.

Orentreich concluded that scalp hairs are donor dominant, our scalp environments do not influence baldness, and that pattern hair loss is most likely a genetically determined process.

His donor dominance theory ruled out any hypothesis that baldness is related to things like scalp tension, low oxygen levels, or skull expansion. Because if those theories were right, the transplanted hairs should have changed behavior when placed in a new environment.

Over the next few decades, other researchers confirmed Orentreich’s results. And thanks to Orentreich’s original research, the hair transplant industry was born.

Today, tens of thousands of men receive a transplant every year – with the overwhelming majority reporting satisfactory results.

But the question remains…

Do hair transplants last forever?

It’s important to note that Norman Orentreich’s original findings were based on observational data that lasted only 2.5 years. What happens in year 5? What about year 10?

We recently set out to answer this question. First, we conducted a literature search to try and identify all research ever published on the subject. Then, we contacted The International Society of Hair Restoration Surgery (ISHRS) to confirm if they were aware of any studies we hadn’t yet identified.

To date, we’ve found just two sources that seemingly attempted to answer this question.

- A 1970 editorial written by Orentreich, who reported that over the past 15 years, “there has been no instance of donor hair-bearing grafts failing to continue hair growth initially accomplished if the donor site is still in an area of the scalp that is growing hair.” [5]https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/4922433/

- A patient satisfaction survey from 1972 for men who had received transplants from 1965 to 1970. In this case, 60% of men reported “no loss of hair from their transplanted sites.” [6]https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/5082373/

This felt odd. Despite more than 60 years of surgical practice and over 10 million hair transplants performed, there’s barely any data that attempts to answer whether hair transplants truly last a lifetime.

What’s more, the data we do have is of low quality. The scant sources we found included just an editorial and a patient survey.

This led us to another question: since Orentreich’s original findings, have we learned anything new about the behavior of human hair transplants over time?

The answer is yes. And not all of it fits perfectly with the theory of donor dominance.

Donor Dominance vs Recipient Site Influence

Since Orentreich’s 1959 publication, researchers have learned a lot more about hair transplants and specifically, the behavior of donor hairs. The findings suggest the theory of donor dominance is not as air-tight as it first seemed. Let’s take a closer look at 3 examples.

Three studies that bring into question the “absolutism” of donor dominance

#1: Scalp hair moved to the leg changes growth characteristics

In 2002, researchers found that over a three-year period hairs taken from the backside of our scalps and moved to our legs had notably lower survival rates.[7]https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12269871/ They also began to grow more slowly.

This contradicted aspects of donor dominance of scalp hairs – which originally asserted that scalp hairs’ growth characteristics do not change when placed into other environments. Yet this study found that scalp hairs moved to the leg (1) had reduced survivability rates relative to other transplant regions, and (2) grew more slowly than non-transplanted scalp hair – thereby more closely mimicking the growth characteristics of other leg hairs.

As such, the researchers hypothesized these transplanted hairs might be influenced by “recipient site characteristics such as vascularity, dermal thickness or skin tension.”

#2: Chest hair moved to the scalp changes growth characteristics

In 2009, a research team transplanted chest hairs into the scalps of men with androgenic alopecia.[8]https://www.ishrs-htforum.org/content/28/6/217.full

They found these chest hairs grew longer and faster on the scalp than they had on the chest. And, just like the previous study, these hairs converged toward the growth characteristics of their new environment.

In other words, chest hairs started behaving differently after being moved to balding regions of the scalp. They converged toward growth characteristics of pre-existing scalp hair.

#3: Completely bald human hair regenerates on the backs of mice

Krajcik, R. A., Vogelman, J. H., Malloy, V. L., & Orentreich, N. (2003). Transplants from balding and hairy androgenetic alopecia scalp regrow hair comparably well on immunodeficient mice. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, 48(5), 752–759.

In 2002, the Orentreich Foundation (yes, the same Orentreich from 1959) conducted a study that took balding human scalp hairs and transplanted them onto the backs of mice.[9]https://www.jaad.org/article/S0190-9622(02)61499-9/references The goal: to see if completely bald human hairs might change behaviors when moved to the backs of mice.

Fascinatingly, those balding human hairs not only completely regenerated, but they did so within a single hair cycle. Moreover, the hairs continued thickening throughout the duration of the study.

This is interesting for a lot of reasons – because research papers have demonstrated that hair regrowth from treatments like finasteride does not involve the conversion of vellus-to-terminal hairs.[10]https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26782302/ Relatedly, after a certain point, there appear to be rate-limiting regrowth factors that prevent conventional hair loss treatments from bringing a miniaturized hair follicle “back from the dead”.[11]https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29407002/ These include step-process failures such as the conversion of stem cells to progenitor cells,[12]https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21206086/ the onset of fibrosis,[13]https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-642-02636-2_3, and the detachment of the arrector pili muscle.[14]https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4158628/

So, the fact that completely vellus human hair follicles can regrow to full thickness in a single hair cycle – just by being moved to the backs of immunodeficient mice – is a significant suggestion that the surrounding environment of these hair follicles likely does matter, and perhaps play a larger role in pattern hair loss than previously believed.

Regardless, each of the above studies indicate the behavior of donor hairs is at least partially influenced by the environment into which they’re transplanted. This is called recipient site influence. And at a minimum, it lends some nuance to the theory of donor dominance.

For these reasons, we should remain critical about hair transplant studies that suggest “permanent results” over a period of time that is less than a single hair cycle… especially given the paucity of well-controlled studies on the subject.

In fact, authors of recent literature reviews for human hair transplants now admit that, contrary to popular belief, transplanted hairs can thin.[15]https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2956960/ It seems, however, that these researchers have found ways to explain why these hair transplants might thin – while still clinging onto the theory of 100% donor dominance.

All of their rationales actually make sense, so let’s dive into them.

Can hair transplants thin and still fit with donor dominance? Yes.

Rationale #1: hairs thin due to bad transplants

Some surgeons argue that poor transplant techniques can decrease hair transplant survivability. This is 100% possible, and it’s partly why different techniques correspond with different survivability thresholds for hairs transplanted from occipital regions to balding parts of the scalp.

Rationale #2: in advanced hair loss, even donor sites can start to thin

In advanced stages of androgenic alopecia, or in cases of diffuse unpatterned hair loss, even donor-safe zones can start to thin. Under these circumstances, donor-safe regions aren’t actually that safe at all, and hairs transplanted from these locations to balding regions will – according to the theory of donor dominance – also undergo miniaturization.

Rationale #3: it’s not donor hairs that are thinning, it’s adjacent hairs

Some surgeons have argued that hair transplants don’t thin at all. Rather, it’s hair surrounding the transplanted hair that thins – giving the impression of losing transplanted hairs (when in reality, the patient is just seeing the overall advancement of pattern hair loss).

These are all plausible explanations, and they certainly explain why transplanted hairs might thin and yet still fit the theory of donor dominance. In order to separate possibility from fact, we’d need to set up a very specific study.

Specifically, we’d need a study that eliminates the possibility of a bad transplant, controls for the “destined to thin” argument, and would remove any ambiguity over the “perception of thinning.”

And we’re in luck, because there has been one study published that (almost) takes all of these possibilities off the table.

2020 Study on Hair Transplant Longevity

In 2020, a study of 112 men with advanced degrees of hair loss, who each received FUT procedures, controlled for nearly every single one of the above factors.[16]https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8061642/

First, the researchers conducted transplants and ensured that, at year one, those transplants grew in just fine. This takes the whole argument of a “bad hair transplant” off the table.

Secondly, those hair transplants were done using FUT procedures. These harvest regions are deep into donor regions whereby most hairs remain protected from pattern hair loss. This reduces the likelihood that any of these hairs would’ve been “destined to thin” in the immediate future.

Third, these researchers performed transplants on men who were in advanced stages of pattern hair loss – Norwood 3.5 and beyond. This meant they were transplanting hairs to mostly barren areas, which reduces the ability to argue that future loss of any hair there is from non-transplanted hairs.

Fourth, these investigators took photographic assessments before the transplant, at the one-year follow-up, and at the four-year follow-up. This allows for us to know (with some degree of certainty) of how these transplanted hairs behaved over time.

Here are the results:

- At one year, over 80% of these men demonstrated good growth of their transplanted hair (so we know their hair transplants worked).

- At four years, over 90% of the men saw a reduction in hair volume. 28% experienced slight thinning of transplanted hairs, 55% had moderate thinning, and 8% showed significant thinning.

In fact, of the 112 men, just 10 showed no loss of transplanted hair density four years after their surgery. See these photos:

Resultantly, these researchers suggested that recipient sites do indeed influence hair transplant outcomes. Further, they postulated that immunological and physiological factors could be influencing donor hairs – including the scalp environment.

In other words: this study strongly suggested that transplanted hairs can thin given enough time… and that this thinning seems to happen faster than loss of hair in donor-safe regions. Just see how healthy the donor regions still look four-years post transplant of the same men featured above:

Corroborating Evidence on Post-Transplant Thinning

While it might seem like the above study runs contrary to years of clinical data on hair transplants, it’s not. Remember:

- Despite millions of hair transplants performed over the last sixty years, well-controlled data on the long-term viability of hair transplants simply does not exist. The longest study we have with an appreciable number of participants is the above 2020 study – and that ran just four years.

- Orentreich’s original hair transplant study ran just 2.5 years. That’s the low-end of a single hair cycle. Hair follicle miniaturization (the defining characteristic of AGA) only happens through hair cycling. So these original studies were not long enough to draw any conclusions.

But there’s something else that’s getting left out of the discussion of all the published clinical data: it’s the clinical experience of actual practicing hair transplant surgeons. And, behind closed doors, nearly all of the surgeons tracking long-term hair transplant outcomes are reporting that hair transplants do not last forever, and that transplanted hair may even thin faster than its donor area.

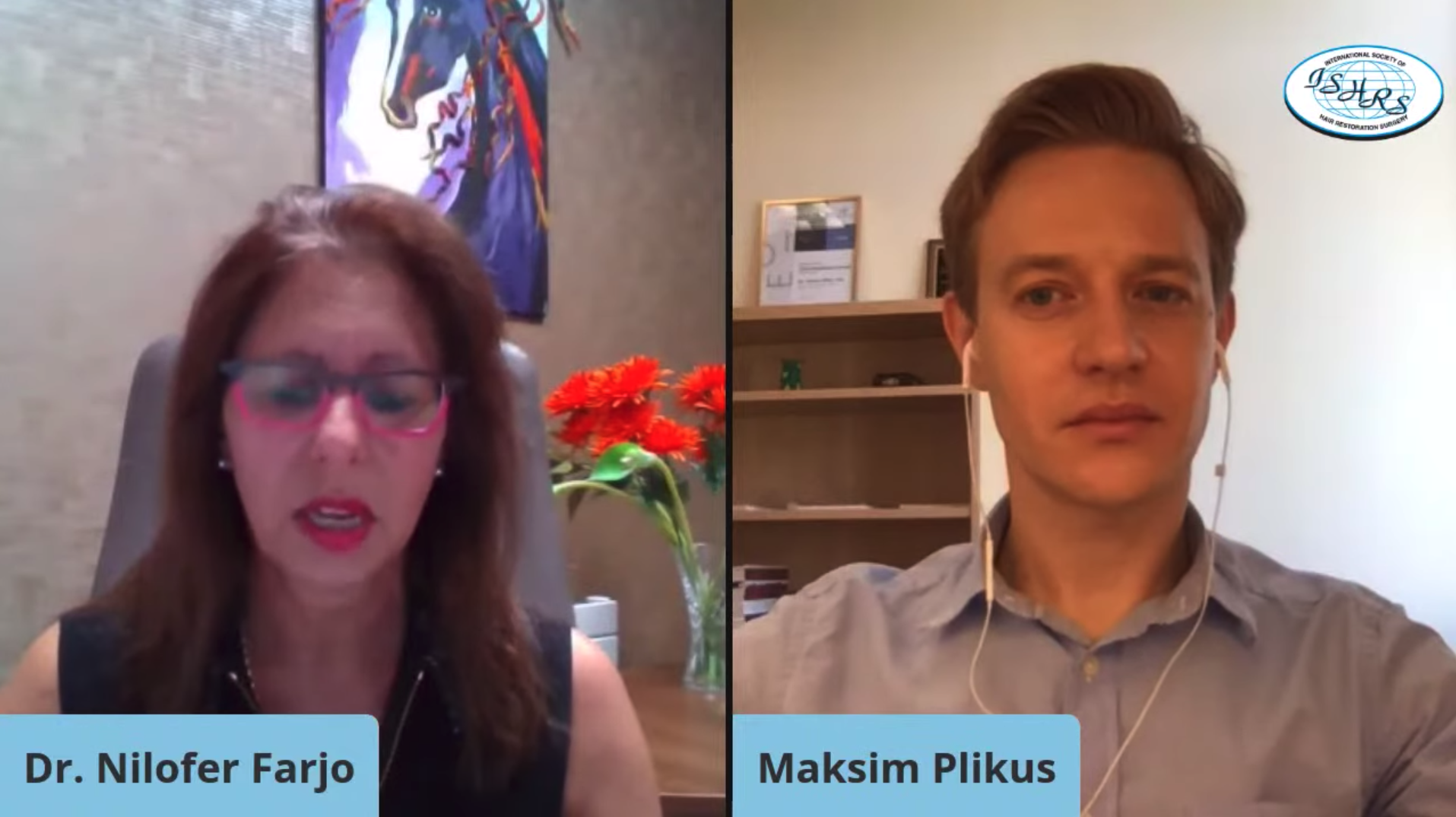

Just ask Dr. Nilofer Farjo – a leading transplant surgeon and the secretary of the ISHRS, or Dr. Maksim Pikus who runs a laboratory at U.C. Irvine specializing in hair loss disorders.

In a recent interview, these two talked openly that, contrary to popular belief:

- Transplanted hairs do thin

- All of their colleagues are seeing it

- The effects likely have something to do with recipient site influence

- The 2-3 year observations on the original hair transplants may not have been long enough to discern the true fate of transplanted hairs

Here are some segments of their discussion:

- “[Regarding] moving occipital hairs to the frontal scalp.[…]We do see over time, those hair follicles that have been moved do change. We often get patients 20 years later who come back and they say their hair follicles were very robust and their hair transplant that looked very thick at the time it was done has now started to thin and doesn’t look the same anymore.” – Dr. Nilofer Farjo, Transplant Surgeon and Secretary of the International Association of Hair Restoration Surgery

- “The dogma in hair transplantation was that occipital hair remained testosterone insensitive, even if they are grafted into otherwise testosterone sensitive recipient areas. And I think, from my reading of hair transplant literature, for the most part that remains true, that the […] cells in the grafted follicles retain their original biology. But […] hairs are also acquiring local signals from the surrounding cells. And perhaps in the beginning after transplantation, most of the signals are acquired from the […] cells that were carried over with the graft. But as years and decades pass, the host tissue becomes more integrated with these hairs, and it’s very possible that the host tissue […] which is also testosterone sensitive secretes what we can define as negative factors.” – Dr. Maksim Plikus, Professor and Researcher, University of California, Irvine

So why, in 2020, are we seeing research that seems to so starkly refute the story of permanence we were told in 1959?

Why the Difference in Results?

Through the early 1970s, Orentreich’s findings regarding hair transplants and donor dominance led to the belief that transplanted hairs are permanent, that scalp environments do not play a role in hair loss, and that balding is likely genetically predetermined within each hair follicle itself.

But over the past two decades, new studies have demonstrated that the environment into which hair is planted indeed has an influence over their behavior, and that balding hairs transplanted to the backs of immunodeficient mice can regenerate in a single hair cycle.

Now, a 2020 study is demonstrating that, contrary to popular belief, over 90% of patients within that study saw thinning of transplanted hairs – and within just a four-year follow up period. These findings are also corroborated by the shared experiences of surgeons like Dr. Nilofer Farjo – who stated that all of her colleagues are seeing transplanted patients 10-15 years later complaining of a loss of their transplanted hair.

So, why is there a discrepancy between the original findings presented by Orentreich and future follow-up studies from 2020? According to our analysis, there are likely two key factors worth discussing:

First, their studies didn’t follow patients for long enough, and second, the hair transplant procedures studied in the 1960s are not the same hair transplant procedures conducted (and studied) today.

This is worth exploring more because it points to a key concept that could initiate breakthrough hair growth treatments.

Why Hair Transplants Thin Over Time

Our hair cycle typically lasts 2 to 7 years. During this process, hairs grow, rest, and shed. From there, the old follicle degenerates, a new follicle regenerates to take its place, and then the process repeats for the rest of our lives.

With this in mind, the way pattern hair loss progresses is through hair follicle miniaturization. That’s when each hair strand gets progressively thinner over time. And this process of miniaturization only occurs through hair shedding.

In pattern hair loss, when the new follicle regenerates, it’s smaller than the last cycle, and so it produces a thinner hair strand. This miniaturization continues with each cycle until the follicle no longer produces hair.

Orentreich’s original study took place after two and a half years. That’s at the low-end of a single hair cycle. In other words, it doesn’t give us enough time to evaluate if transplanted hairs were thinning. To see that, we’d need to observe multiple hair cycles. And because hair cycles last 2-7 years, that means a valuable long-term study would have a duration of at least 10-15 years.

The researchers who closely followed Orentreich fared no better. Most studies from this era define ‘long-term’ as 2-4 years. This simply never allowed us to gather useful data regarding the lifelong viability of hair transplants.

Advances in Grafting Techniques

Orentreich’s donor dominance theory claimed hair transplants should last a lifetime, as long as the donor site was from an area protected from baldness. Assuming he missed the truth because his follow-up study was just a short 2.5 years after transplantation, why didn’t he see conflicting evidence over the course of the following 10-20 years?

In 1970, he even wrote an opinion piece stating that over the last 15 years, “there has been no instance of donor hair-bearing grafts failing to continue the hair growth initially accomplished if the donor site is still in an area of the scalp that is growing hair.”[17]https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/4922433/

Given Norman Orentreich’s incredible contributions to medicine, we have no reason to believe that he lied about his observations. So, what might explain the differences in Orentreich’s observations from the 1970’s about hair transplant permanence versus the observations from today, according to that 2020 paper and the interview with Nilofer Farjo?

The answer could be in the way transplants are done today versus the 1960’s.

Methodological differences in hair transplants (1960’s vs. today): punch graft size

Early surgeries typically transplanted 3.5-4 mm punch biopsies containing dozens of hair follicles. Modern-day transplants, on the other hand, are done with grafts as small as 0.8 mm. These grafts are so small they often contain just a single strand of hair.

Punch graft differences in human hair transplants: today versus 1960

This does have its benefits, as it prevents the old ‘hair plug’ look of the 1960s and minimizes scarring. However, does it make today’s hair transplants somehow less permanent than those that Orentreich would have observed? The answer appears to be yes.

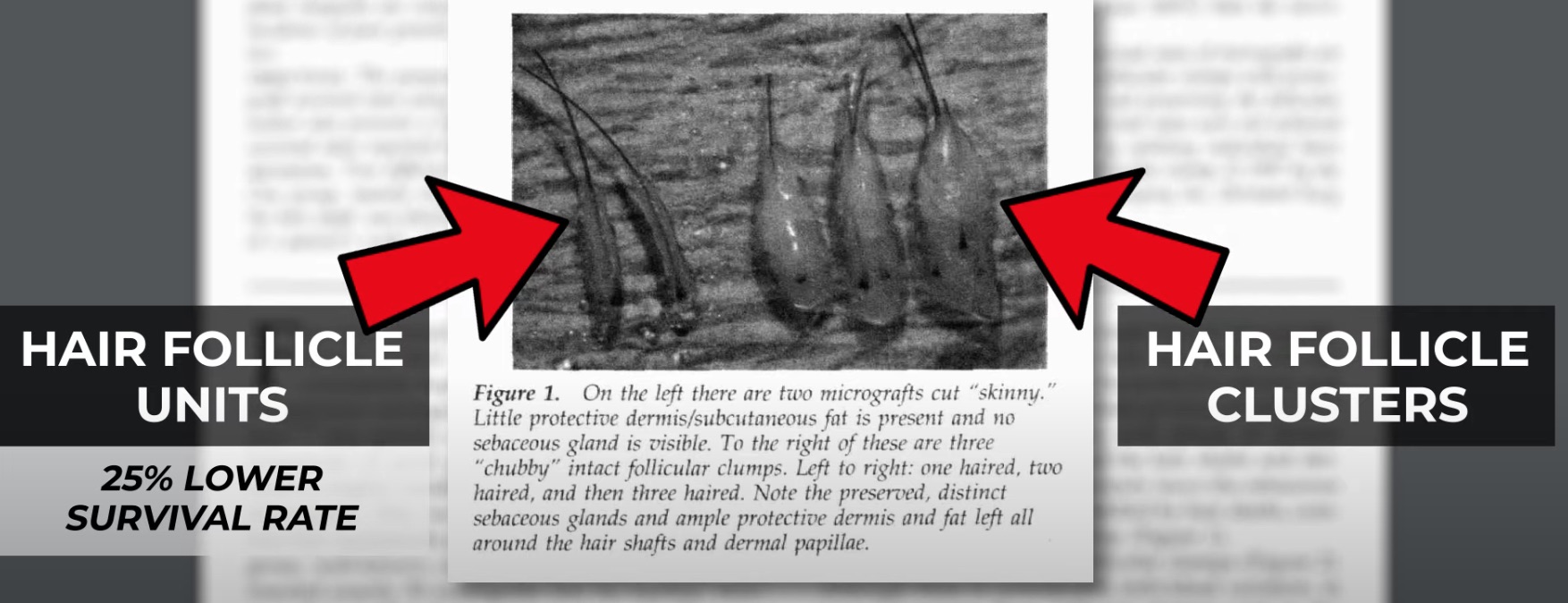

Research indicates the amount of skin and fat tissue we carry surrounding a hair transplant influences its survivability. Just see these studies that measured whether the volume of tissue transplanted alongside a transplanted hair follicle had any effect on transplant survivability:[18]https://www.ishrs-htforum.org/content/23/1/1[19]https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9311369/

To put it bluntly: multiple studies demonstrate that the survivability of hair transplants is directly influenced by the amount of surrounding tissue transferred with the hair. The less tissue, the lower the survival rate. The more tissue, the higher the survival rate.

Seager D. J. (1997). Micrograft size and subsequent survival. Dermatologic surgery : official publication for American Society for Dermatologic Surgery [et al.], 23(9), 757–762.

This suggests that, in human hair transplants, the surrounding tissue transferred alongside transplanted hair follicles may act as a buffer against recipient site influence.

Now let’s take a look back at Orentreich’s original paper. How big were the punch grafts he used? The punch grafts he transplanted were between 6 to 12 mm in width. That’s a massive amount of tissue. Just see the figure photo from his paper:

Not only does this photo show just how barbaric the original hair transplants were, but it also shows how much skin was actually transferred alongside these hair follicles: substantial skin tissue containing dozens and dozens of hair follicles with each transplant.

Reflecting on these methodological differences, it’s reasonable to surmise that Orentreich’s original transplants probably didn’t thin – at least not at the rate suggested in the 2020 study. In the 1960’s and 1970’s, transplant surgeons were transplanting hair follicle clusters alongside 3-12 mm of skin tissue. In the transplants today, transplant surgeons are transplanting hair follicle singlets along with 0.8mm of skin tissue – sometimes even less.

Summary: How Long Hair Transplants Really Last

Although early researchers asserted that hair transplants lasted a lifetime, these presumptions were built on:

- Studies that ran just 2.5 years (that’s the low end of a single hair cycle)

- Studies that transferred substantial amounts of surrounding skin tissue with each hair transplant (i.e., 3-12 mm).

Today, not much research exists on the longevity of human hair transplants. Of the data that we do have, evidence shows that, contrary to originally believed, hair transplants do thin – with one 2020 study showing that over 90% of hair transplants showed cosmetic degrees of loss just four years post-surgery. While researchers have not fully worked out why this is the case, it’s likely that it has at least something to do with the fact that hair transplants of today typically only insert hair follicle units or clusters with just 0.8-1.2 mm of tissue surrounding them, versus the 3-12 mm transferred in the early days of transplant research.

Moreover, at least three studies over the last two decades have revealed that:

- Human scalp hair changes hair growth speeds when moved to the leg.

- Chest hair moved to the scalp also changes growth speeds.

- Bald human hair follicles can regenerate in a single hair cycle when moved to the backs of immunodeficient mice.

These studies are now creating some nuance to the theory of donor dominance – and introducing concepts of recipient site influence to the world of scalp hair and androgenic alopecia.

So, are hair transplants even worth the cost?

In nearly all cases, the answer is yes. Studies demonstrate that hair transplants significantly improve someone’s quality of life, and that the procedure is often worth the investment (at least for those who are capable of affording them).

Having said that, the data also suggest that if you are going to get a transplant, you should probably simultaneously seek medical treatment for androgenic alopecia so that you can protect your investment! Find a regimen that fits with your needs and preferences so that you can stave off the progression of pattern hair loss and make the transplant as financially and physiologically impactful as possible. Finasteride is one option, but there are dozens of others discussed in our membership program.

Recipient sites probably do influence the fate of transplanted hairs. But with the right surgeon, the right plan, and the right hair loss type, transplanted hair can last a very long time.

References[+]

References ↑1, ↑4 https://nyaspubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1749-6632.1960.tb40920.x ↑2 https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamaotolaryngology/article-abstract/603301 ↑3 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33911409/ ↑5, ↑17 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/4922433/ ↑6 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/5082373/ ↑7 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12269871/ ↑8 https://www.ishrs-htforum.org/content/28/6/217.full ↑9 https://www.jaad.org/article/S0190-9622(02)61499-9/references ↑10 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26782302/ ↑11 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29407002/ ↑12 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21206086/ ↑13 https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-642-02636-2_3 ↑14 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4158628/ ↑15 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2956960/ ↑16 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8061642/ ↑18 https://www.ishrs-htforum.org/content/23/1/1 ↑19 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9311369/ Want help with your hair regrowth journey?

Get personalized support, product recommendations, video calls, and more from our researchers, trichologists, and PhD's dedicated to getting you the best possible outcomes.

Learn More

Perfect Hair Health Team

"... Can’t thank @Rob (PHH) and @sanderson17 enough for allowing me to understand a bit what was going on with me and why all these [things were] happening ... "

— RDB, 35, New York, U.S.A.

— RDB, 35, New York, U.S.A."... There is a lot improvement that I am seeing and my scalp feel alive nowadays... Thanks everyone. "

— Aayush, 20’s, Boston, MA

— Aayush, 20’s, Boston, MA"... I can say that my hair volume/thickness is about 30% more than it was when I first started."

— Douglas, 50’s, Montréal, Canada

— Douglas, 50’s, Montréal, CanadaWant help with your hair regrowth journey?

Get personalized support, product recommendations, video calls, and more from our researchers, trichologists, and PhD's dedicated to getting you the best possible outcomes.

Join Now - Mission Statement