- About

- Mission Statement

Education. Evidence. Regrowth.

- Education.

Prioritize knowledge. Make better choices.

- Evidence.

Sort good studies from the bad.

- Regrowth.

Get bigger hair gains.

Team MembersPhD's, resarchers, & consumer advocates.

- Rob English

Founder, researcher, & consumer advocate

- Research Team

Our team of PhD’s, researchers, & more

Editorial PolicyDiscover how we conduct our research.

ContactHave questions? Contact us.

Before-Afters- Transformation Photos

Our library of before-after photos.

- — Jenna, 31, U.S.A.

I have attached my before and afters of my progress since joining this group...

- — Tom, 30, U.K.

I’m convinced I’ve recovered to probably the hairline I had 3 years ago. Super stoked…

- — Rabih, 30’s, U.S.A.

My friends actually told me, “Your hairline improved. Your hair looks thicker...

- — RDB, 35, New York, U.S.A.

I also feel my hair has a different texture to it now…

- — Aayush, 20’s, Boston, MA

Firstly thank you for your work in this field. I am immensely grateful that...

- — Ben M., U.S.A

I just wanted to thank you for all your research, for introducing me to this method...

- — Raul, 50, Spain

To be honest I am having fun with all this and I still don’t know how much...

- — Lisa, 52, U.S.

I see a massive amount of regrowth that is all less than about 8 cm long...

Client Testimonials150+ member experiences.

Scroll DownPopular Treatments

Scroll DownPopular Treatments- Treatments

Popular treatments. But do they work?

- Finasteride

- Oral

- Topical

- Dutasteride

- Oral

- Topical

- Mesotherapy

- Minoxidil

- Oral

- Topical

- Ketoconazole

- Shampoo

- Topical

- Low-Level Laser Therapy

- Therapy

- Microneedling

- Therapy

- Platelet-Rich Plasma Therapy (PRP)

- Therapy

- Scalp Massages

- Therapy

More

IngredientsTop-selling ingredients, quantified.

- Saw Palmetto

- Redensyl

- Melatonin

- Caffeine

- Biotin

- Rosemary Oil

- Lilac Stem Cells

- Hydrolyzed Wheat Protein

- Sodium Lauryl Sulfate

More

ProductsThe truth about hair loss "best sellers".

- Minoxidil Tablets

Xyon Health

- Finasteride

Strut Health

- Hair Growth Supplements

Happy Head

- REVITA Tablets for Hair Growth Support

DS Laboratories

- FoliGROWTH Ultimate Hair Neutraceutical

Advanced Trichology

- Enhance Hair Density Serum

Fully Vital

- Topical Finasteride and Minoxidil

Xyon Health

- HairOmega Foaming Hair Growth Serum

DrFormulas

- Bio-Cleansing Shampoo

Revivogen MD

more

Key MetricsStandardized rubrics to evaluate all treatments.

- Evidence Quality

Is this treatment well studied?

- Regrowth Potential

How much regrowth can you expect?

- Long-Term Viability

Is this treatment safe & sustainable?

Free Research- Free Resources

Apps, tools, guides, freebies, & more.

- Topical Finasteride Calculator

- Interactive Guide: What Causes Hair Loss?

- Free Guide: Standardized Scalp Massages

- 7-Day Hair Loss Email Course

- Ingredients Database

- Interactive Guide: Hair Loss Disorders

- Treatment Guides

- Product Lab Tests: Purity & Potency

- Evidence Quality Masterclass

More

Articles100+ free articles.

-

Cannabidiol (CBD) Increases Hair Counts By 246%? Not So Fast.

-

Creatine: Does It Worsen Hair Loss? It Depends On The Hair Loss Type.

-

Can Progesterone Improve Hair Regrowth?

-

CRABP2: Can This Gene Predict Regrowth From Retinoids?

-

BTD: Can This Gene Predict Regrowth From Biotin?

-

COL1A1: Can This Gene Predict Regrowth From Collagen Support?

-

2dDR For Hair Loss: What Do We Know So Far About This Sugar?

-

CYP19A1: Can This Gene Predict Regrowth From Hormone Therapy?

PublicationsOur team’s peer-reviewed studies.

- Microneedling and Its Use in Hair Loss Disorders: A Systematic Review

- Use of Botulinum Toxin for Androgenic Alopecia: A Systematic Review

- Conflicting Reports Regarding the Histopathological Features of Androgenic Alopecia

- Self-Assessments of Standardized Scalp Massages for Androgenic Alopecia: Survey Results

- A Hypothetical Pathogenesis Model For Androgenic Alopecia:Clarifying The Dihydrotestosterone Paradox And Rate-Limiting Recovery Factors

Menu- AboutAbout

- Mission Statement

Education. Evidence. Regrowth.

- Team Members

PhD's, resarchers, & consumer advocates.

- Editorial Policy

Discover how we conduct our research.

- Contact

Have questions? Contact us.

- Before-Afters

ArticlesWhat Is Post-Finasteride Syndrome (PFS)? Is It Real? And What Is Its Prevalence?

First Published Feb 16 2023Last Updated Oct 29 2024Pharmaceutical Researched & Written By:Perfect Hair Health Team

Researched & Written By:Perfect Hair Health Team Reviewed By:Rob English, Medical Editor

Reviewed By:Rob English, Medical Editor

Want help with your hair regrowth journey?

Get personalized support, product recommendations, video calls, and more from our researchers, trichologists, and PhD's dedicated to getting you the best possible outcomes.

Learn MoreArticle Summary

Post-Finasteride Syndrome (PFS) is a term used to describe persistent sexual or cognitive side effects from finasteride, even months after quitting the medication. The existence of PFS is hotly debated amongst hair loss researchers, endocrinologists, and dermatologists. In this article, we’ll explore some of the science-based arguments on both sides of the PFS debate.

Full Article

Post-Finasteride Syndrome is a term used to describe a constellation of symptoms reported by former finasteride users who quit using the drug, but who still report drug-related side effects more than 3 months after discontinuing.

Amongst dermatologists, endocrinologists, and hair loss researchers, the existence and prevalence of Post-Finasteride Syndrome (PFS) is a hotly debated topic. On the one hand, some urologists like Dr. Abdulmaged Traish are adamant that PFS is real, and that the original clinical trials that earned finasteride FDA approval were neither adequately designed nor robust enough to capture how many finasteride users might be affected.[1]https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32033719/

On the other hand, some world-renowned hair loss researchers like Dr. Ralph Trueb claim that PFS is a self-induced delusional disorder bordering on mass formation psychosis – and support those claims by pointing to (1) the absence of evidence of PFS from the original finasteride studies, (2) the influence of media reporting on PFS and subsequent spikes in people claiming to have the condition, and (3) a strong proclivity toward those claiming to have PFS also having diagnosed mental health disorders – particularly histrionic personality disorder.[2]https://www.karger.com/Article/Fulltext/497362

So, what’s the truth about PFS? Is it real or imagined? If PFS is real, what’s the estimated risk for people trying finasteride? And is there anything that can be done to lower the risk of PFS?

In this article, we’ll explore the evidence on both sides of the PFS argument, explain why the existence of PFS is difficult to study, and reveal why debate over PFS is likely here to stay. Finally, we’ll contextualize the estimated prevalence of PFS by comparing its risk ratio to other voluntary risks taken in each day of life – like the risk of death from driving a motor vehicle – all so that potential finasteride users can make more informed decisions about their hair loss treatments.

What Is Post-Finasteride Syndrome (PFS)?

Post-Finasteride Syndrome (PFS) is an alleged condition from the use of finasteride, whereby side effects incurred from the drug do not go away 3+ months after quitting. The implication of PFS is that, for a very small number of finasteride users, side effects might be long-lasting, and perhaps permanent.

Alleged PFS symptoms vary from person-to-person, but in general, may involve persistent and unresolved:

- Sexual dysfunction

- Genital numbness

- Reduced libido and/or weak erections

- Persistent brain fog

- Depressive-like symptoms

Some people claiming to experience PFS-related side effects have described their onset within hours of taking a single finasteride pill. Others say it took months before anything started going wrong. Others say they were symptom-free while using finasteride, and that they only started experiencing side effects after withdrawing from the drug.

Given the heterogeneity in both PFS symptoms and their timings of onset, researchers (and sufferers) have struggled to understand why this alleged condition seems to impact so many people in such wildly different ways.

Nonetheless, those who believe PFS is real also suspect that its development is causally linked to the enzyme that finasteride inhibits, as well as the potential for that enzyme inhibition to have unintended, downstream, long-lasting effects on the body.

Finasteride & Side Effects: A History Of Debate

Finasteride is a drug that inhibits the type II 5-alpha reductase enzyme. By inhibiting this enzyme, finasteride lowers levels of dihydrotestosterone (DHT) – a hormone causally associated with androgenic alopecia (AGA) and benign prostatic hyperplasia.

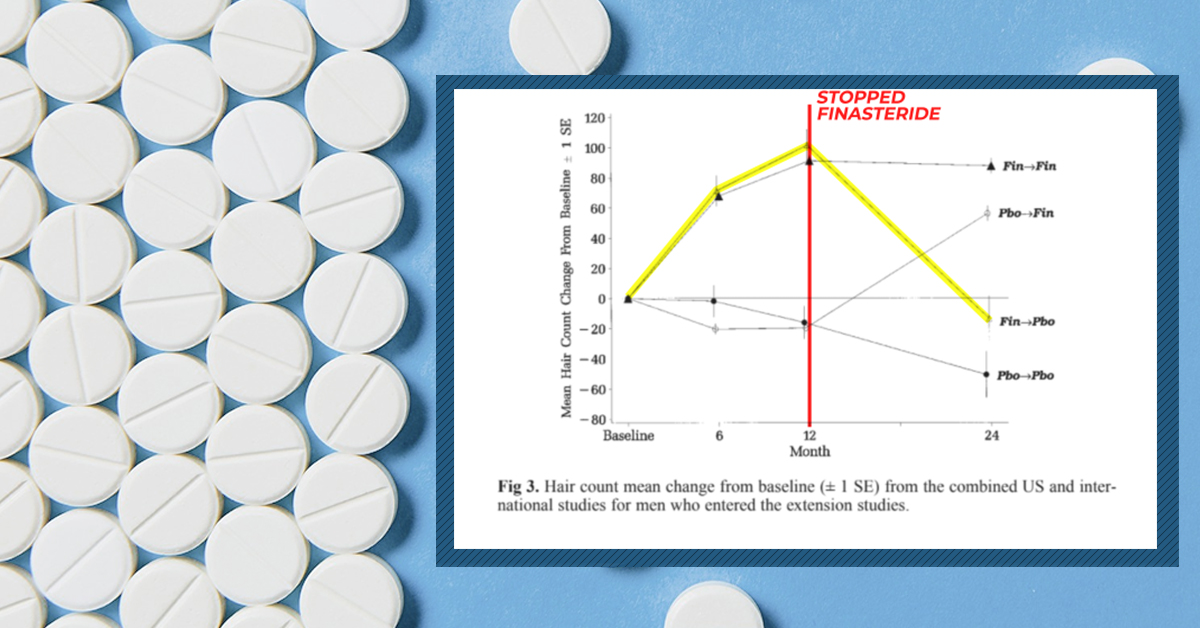

At daily doses of 0.2 mg to 5.0 mg daily, oral finasteride can therapeutically lower DHT levels by 70% – with two-year studies showing that 80-90% of men using the drug see a slowing, stopping, or partial reversal in AGA.[3]https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0022202X15529357 In fact, dozens of studies totaling more than 10,000 participants suggest that oral finasteride routinely improves hair growth outcomes versus placebo – with 5- and 10-year studies suggesting hair maintenance above baseline for a majority of its users.[4]https://www.oatext.com/Long-term-(10-year)-efficacy-of-finasteride-in-523-Japanese-men-with-androgenetic-alopecia.php

For these reasons (and the quality of evidence supporting the medication), finasteride has received FDA-approval for AGA and is widely considered the gold-standard medical intervention for this condition.

But as is the case with all medications, there’s always a risk of side effects. For finasteride, these side effects tend to present in the form of lowered libido, sexual dysfunction, gynecomastia, and/or brain fog.

While the original clinical trials that granted finasteride FDA-approval estimated side effect risks to be less than 5% versus placebo, follow-up studies have put that risk as high as 40%.[5]https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0022202X15529357[6]http://www.drproctor.com/propecia/propecia.pdf Depending on the online resource you read (i.e., a natural website versus a telehealth website), you may have noticed that websites will cite either end of the extreme, depending on the products they’re trying to sell. Natural websites tend to cite higher numbers to fearmonger over side effects and encourage people to buy their natural supplements and topicals; telehealth websites tend to avoid discussions about higher estimations because it might interfere with prescription drug sales.

The reality is that most follow-up studies citing higher rates of finasteride-related side effects tend to be of lower quality – with smaller sample sizes, biases in research methodologies, and a strong influence of the nocebo effect – whereby in some studies, physicians actually told patients to “watch out” for side effects while prescribing the drug, which introduces a psychogenic influence whereby patients become nearly 5 times as likely to report those side effects.[7]https://www.nature.com/articles/ncpuro1012

At the same time, other researchers have pointed out that finasteride’s original clinical trials also contain their own biases. For instance, those studies were funded by Merck – the very drug company that stood to gain from the approval of its patented hair loss-fighting medication – and that this might’ve influenced the ways in which side effects were both catalogued and tabulated by investigators – all to downplay their true prevalence and/or magnitude.

While these criticisms may read as conspiratorial and unfounded, the reality is that Merck doesn’t have the best reputation as a drug company. Former employees-turned-whistleblowers alleging clinical trial obfuscation in vaccine trials, and lawsuits settled after drugs taken to market by Merck later inadvertently killed lots of people.[8]https://www.fiercepharma.com/vaccines/whistleblowers-accuse-merck-of-withholding-info-on-mumps-vaccine[9]https://www.nature.com/articles/450324b Because of this history, criticisms of this nature will remain on-the-table for Merck, regardless of their validity.

Based on our experience working with hair loss sufferers (and our read of the data), we estimate that between 5% to 15% of finasteride users experience some degree of side effects – and that the majority of these side effects are mild and improvable – at least with the right titration and/or drug delivery strategies. If you’re interested in learning more, see our article on strategies to reduce side effects from finasteride, and if blood tests can help predict finateride-linked side effects.

Nonetheless, it is true that a small subset of finasteride users do experience side effects, and that many of those side effects are sexual or cognitive in nature. What is debated, however, is whether those finasteride-induced side effects reverse entirely for 100% of people after quitting the medication.

According to finasteride’s phase II and phase III clinical trials, all participants who stopped using finasteride due to side effects saw a complete resolution of those side effects, and within three months. Yet in the last 15 years, some former finasteride users have claimed otherwise.

So what might explain this discrepancy? And if this phenomenon is real, how might we explain its pathology?

Post-Finasteride Syndrome: What Might Cause It?

To date, there have been dozens of hypotheses surrounding how PFS might develop. All of them relate to the way finasteride works, and what might go wrong when the enzyme the drug targets is inhibited for appreciable periods of time.

Below are three theories that have received significant attention over the last few years, along with their counterarguments.

Please consider this a very brief overview of these arguments. The goal of this article is not to indoctrinate ourselves within the fine details of these hypotheses, but instead, to overview both sides of the argument, explain why this debate won’t be settled anytime soon, express our current perspectives given the data, and reveal strategies to navigate any known-unknown risks linked to finasteride.

Persistent biological changes (i.e., androgen receptor upregulation and/or downregulation)

- Argument: In vitro and animal studies suggest that when anti-androgen drugs – like spironolactone, finasteride, or flutamide – are administered, male hormones (like testosterone or dihydrotestosterone) decrease, and in response, androgen receptors increase.[10]https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3116931/[11]https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21557276/ In some animal models, withdrawal from anti-androgen drugs does not lead to a rebalancing of androgen receptor expression. In other words, these receptors remain upregulated. This suggests long-lasting biological changes from finasteride use might be possible in a small subset of users, and that androgen receptor upregulation (or reflexivity) might be part of the equation for those suffering from PFS.[12]https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34247957/

- Counterargument: Human data on finasteride use and androgen receptor upregulation often conflicts with findings from in vitro and animal models.[13]https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4137476/ Moreover, animal models whereby androgen receptors remained upregulated following finasteride withdrawal (1) used supraphysiological doses of finasteride, and (2) paired that drug with other anti-androgens. This doesn’t reflect normal human usage cases, and co-administration of the drugs obfuscates the ability to discern which drug is actually responsible for the phenomenon. Finally, studies on finasteride show that serum and tissue DHT levels return to normal following ~30 days of treatment withdrawal. This suggests that if finasteride is leading to any androgen receptor reflexivity or permanent upregulation, then for whatever reason, hormonal levels post-finasteride withdrawal still return to baseline.[14]https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK513329/ Finally, studies exploring the potential for upregulation of androgen receptors in penile tissues of those claiming PFS do not use adequate controls – such as men affected by erectile dysfunction who never used the drug. Therefore, it is impossible to parcel out how many of these cases are drug-related versus just related to impotence – which affects a high number of American adults.

Persistent changes to gut microflora

- Argument: Observational studies on PFS sufferers show alterations to gut microflora versus healthy controls.[15]https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32951160/ These gut alterations in microflora might influence hormonal and immunological markers elsewhere throughout the body – particularly the skin tissues and brain. After all, studies show bidirectional feedback loops between gut microflora and serum / organ hormonal profiles, which are causally linked to disorders related to libido and mood.[16]https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6962501/

- Counterargument: While this is hypothetically plausible, the one study measuring gut microflora composition on post-finasteride syndrome participants suffers from major methodological flaws – one of the biggest being a negative-control group. For instance, depression also influences gut microflora, but depressed patients were not included as a negative control in this study. How can we discern the differences between these depressed patients and any long-lasting microflora changes due to withdrawn finasteride use? Due to the limitations of this study, it’s impossible to further this hypothesis with the available data.

Persistent histological changes (i.e., tissue fibrosis and scarring)

- Argument: Subsets of PFS sufferers have reported tissue-level changes appearing since their first use of finasteride. These histological changes include, but are not limited to, penile microvascular changes and fibrosis.[17]https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7354335/ There is mechanistic evidence suggesting that low DHT levels in prostatic tissues might elevate inflammatory markers that could resolve, over time, into fibrosis if left unchecked.[18]https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3997870/ Therefore, perhaps PFS is caused by medically lowering DHT levels, which in a subset of patients, might increase inflammation that leads to scarring in key organ sites. When the medication is withdrawn, DHT levels return to normal, but the fibrosis / scarring that formed during the hormone’s depression remains.

- Counterargument: While this hypothesis warrants further investigation, the studies supporting this viewpoint are of very low quality due to small sample sizes and no control groups. It is important to note that upwards of 40% of American adults suffer from erectile dysfunction – with increasing prevalence per decade of life and a subset of those individuals also displaying with penile fibrosis.[19]https://www.amjmed.com/article/S0002-9343(06)00689-9/fulltext[20]https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8254833/ Without a control group, these studies make it impossible to parcel out who might believe they’re experiencing long-standing side effects from finasteride, but who are just coincidentally reaching the age at which impotence risk increases, and by coincidence of usage and the very fact that finasteride can cause sexual side effects, these participants are misplacing blame on the drug for a phenomenon that would’ve otherwise happened to them had they never used the drug anyway. Furthermore, there is no high-quality evidence of long-lasting histological changes in finasteride users after withdrawing from the drug. All indications are that hormonal profiles return to normal, and that even while on the drug, muscle morphology and subcutaneous fat stores do not change relative to controls because testosterone and other hormones can still govern these processes in replacement to lowered DHT.

Summarizing The Case Against PFS

There are rebuttals to these counterarguments, and counter-rebuttals to those rebuttals. But given these arguments and counterarguments, we’ve likely seen enough to recognize their overarching patterns:

- Yes, there’s some mechanistic and clinical evidence to support the anecdotes of symptoms befitting PFS. But…

- That evidence is of very low quality, so will remain forever scrutinized (and with good reason)

For instance, some mechanistic studies conflict with human studies, and due to small sample sizes, imperfect methodologies, and inadequate control groups, the PFS clinical studies currently available will remain open to criticism.

Moreover, because the original 1-, 2-, and 5-year studies on finasteride did not report (in their published material) any incidences of side effects not resolving after a participant withdrew from treatment, it’s incredibly difficult to parcel out finasteride’s influence on persistent erectile dysfunction versus the background risk of erectile dysfunction in adult men – which some studies suggest is 40% or higher.

Finally, PFS reports increase and decrease in congruence with media coverage on the topic, along with lawsuits against Merck for men who claim to be experiencing PFS-like effects.[21]https://www.karger.com/Article/Fulltext/497362 For what it’s worth, studies show that finasteride users have a strong tendency toward the nocebo effect – whereby simply telling a patient about the drug’s side effects leads to those patients reporting those side effects at a much higher rate than had they never been told anything. This was demonstrated in a randomized, controlled clinical study whereby a group of men who were prescribed finasteride and told it might lower their libido were nearly 500% more likely to report sexual side effects in follow-up appointments versus those who hadn’t been told that information.[22]https://www.nature.com/articles/ncpuro1012

All of this makes it scientifically challenging to parcel out a true prevalence of PFS, or even catalogue the condition as real versus imaged.

5 Barriers In The Way Of Proving PFS’ Existence

Take into consideration the following realities:

- The strong nocebo influence of finasteride

- The influence of media on PFS reporting

- The high background rates of erectile dysfunction and/or impotence in adults

- The fact that many PFS sufferers have mental health disorders – like histrionic personality disorder

- The very low quality studies exploring PFS

Given these circumstances, it might feel reasonable to dismiss PFS as a hoax condition propagated by opportunistic, delusional men looking to cash in by filing frivolous lawsuits against a pharmaceutical giant.

In fact, this is essentially the sentiment on most public hair loss forums – BaldTruthTalk, HairLossTalk and Tressless – whose users routinely mock and insult people alleging PFS, and in doing so, dissuade discussion about the topic.

If you hold this sentiment, it’s not unreasonable – particularly given the studies, arguments, and counterarguments we just outlined.

Yes, there’s reason to doubt the existence of PFS. Yes, there’s reason to question the sanity of many alleged PFS sufferers.

But that’s not the whole story.

One of the biggest counterarguments for PFS – one routinely repeated online – is actually inaccurate. Most people wouldn’t know it, mainly because of the sheer number of people blindly regurgitating it on hair loss forums.

It’s the assertion that there’s no evidence that finasteride can cause histological changes that persist after quitting the drug.

This is 100% false.

There is evidence of persistence histological changes post-finasteride withdrawal. In fact, these changes are well-studied and widely acknowledged by physicians across both aisles of the PFS debate.

The phenomenon is called finasteride-induced gynecomastia. And in a subset of cases, it doesn’t resolve after quitting the drug.

Persistent Gynecomastia: The Strongest Evidence Supporting Post-Finasteride Syndrome

Gynecomastia is the growth of male breast tissue. In men, studies causally link the development of gynecomastia to elevations in estrogen and/or prolactin.

Men who use finasteride tend to see their levels of estradiol (an estrogen) increase by 10-20%. This is a normal consequence of 5-alpha reductase inhibition, because with less available DHT formation, more free testosterone will convert into total testosterone and estradiol.

For those who have a genetic predisposition to gynecomastia, or for those whose diets, lifestyles, and environments have already elevated their estrogen and/or prolactin beyond baseline, any additional increases in estrogen from finasteride might be enough to push these men toward the development of unwanted growth of breast tissue.

This is a well-studied side effect of finasteride (and 5-alpha reductase inhibitors). It tends to affect between 0.25% to 5% of finasteride users – with a varying magnitudes of effect and prevalence depending a study’s participants (i.e., healthy young men or overweight men with benign prostatic hyperplasia).[23]https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23067029/

To be clear: there is no debate over finasteride-induced gynecomastia, or the mechanisms governing its development.

So, let’s circle back to one of the biggest counterarguments levied by people who do not believe in the plausibility of PFS.

If gynecomastia occurs in a small subset of finasteride users, then once someone stops taking finasteride, that gynecomastia should go away. Right?

Wrong.

Clinical studies show that in 80% of cases, finasteride-induced gynecomastia resolves if given enough time away from the drug.[24]https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2929552/[25]https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamadermatology/article-abstract/478759 Having said that, 20% of cases may see incomplete or no resolution – even up to six years after quitting the medication.[26]https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2929552/

Under those circumstances, the only option for removal is surgery.

Persistent gynecomastia is perhaps the best example of a long-lasting histological change caused by finasteride that does not always resolve after the drug is discontinued.

The histological change is the unwanted growth of adipose and/or glandular tissue in the male breast.

This phenomenon is well-defined, well-observed, and widely-recognized amongst researchers on both sides of the PFS debate. And while the original finasteride studies did not capture this risk, post-marketing studies did.

This is because those original finasteride studies – despite having more than 1,200 participants in the finasteride group – still weren’t large enough to account for a side effect rare enough to impact only one-fifth of 0.25% of healthy finasteride users (i.e., 1 in every 2,000 people).[27]https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0190962298700076

With that in mind, let’s revisit the possibility and plausibility of PFS. If there are cases of finasteride-induced gynecomastia that persist even after finasteride is discontinued, does this signal that finasteride might also have a potential to histologically influence other organ sites in similar matters?

Yes.

And while these types of adverse events (if they do exist) are probably incredibly rare – much like persistent gynecomastia induced by finasteride – their existence is now plausible, because we’ve seen a similar phenomenon documented in male breast tissue.

Why The PFS Debate Is Here To Stay

In the exercise above, we revealed how an incredibly rare adverse event from finasteride – treatment-induced gynecomastia that persists even after quitting the drug – is now a recognized side effect that was not captured in the original clinical studies on finasteride. Instead, it was a side effect observed in post-marketing studies – mainly because of how few people it affects: perhaps just 1 in every 2,000 finasteride users.

Given the heated scientific debate over PFS versus the well-established acknowledgment of finasteride-induced gynecomastia, it’s probably safe to assume that if PFS is real, the number of finasteride users affected is substantially less than 1 in 2,000.

Otherwise, PFS would’ve probably been noted in finasteride’s original phase II and phase III clinical trials.

So, let’s assume (for the sake of argument) that the estimated prevalence of PFS is 1 in 5,000 finasteride users. Let’s also assume that around 40% of American adult men already have some degree of impotence – which has previously been established by several studies.

What sort of study do we need to design to prove or disprove the existence of PFS?

We would need a study that was randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled, and prospectively designed – as these kinds of studies are generally the only types that can infer causality.

One group of people would receive finasteride; the other group would receive a sugar pill. The study would need to run multiple years – to control for the heterogeneity in timings of onset for PFS. And it would also need a multiple-year withdrawal period to track outcomes for side effect resolution.

So, how many participants would we need to gain enough statistical power to get a definitive answer?

This is where things get incredibly difficult to parcel out.

If we estimate a “true” PFS incidence of 1 in 5,000 finasteride users (i.e., 0.02%), we must recruit enough men in this study to statistically differentiate that effect from the background risk of erectile dysfunction in 40% of adult men.

With randomization, erectile dysfunction should be equally present in both finasteride users and non-users, and at a background rate of 40%. So, we’ll need a large enough sample size to discern statistical significance between impotence reports with differences of 40% (in the placebo group) versus 40.02% (erectile dysfunction + PFS post drug withdrawal).

Then we’ll need to also find ways to account for risks of the nocebo effect and mental health disorders influencing side effect reporting – as some participants will ultimately discover that they’re using finasteride and begin researching the drug on their own. There are statistical tools that can help us account for all of the above to determine a needed sample size for significance.[28]https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4017493/

So, accounting for all of the above, how many participants do we need to recruit to determine – once and for all – if PFS is real?

1,000,000+ participants.

That’s right. We need more than a million study participants. That’s how much work it will take to parcel out a 0.02% increased risk of finasteride-induced erectile dysfunction persisting post-drug withdrawal from the 40% background risk of already having erectile dysfunction or having it develop for unrelated reasons during the time someone is using the medication.

That sort of study would require billions of dollars to fund, and even if it were funded, we wouldn’t have an answer until years after the study began – probably 5-10 years after its initiation.

Keep in mind that finasteride’s patent expired years ago. With these financial barriers and with no incentive for funding from large pharmaceutical companies, the likelihood of this study happening is as close to 0% as it gets.

For these reasons, debate over PFS is destined to rage on. The studies to prove or disprove its existence are too difficult to conduct.

Reconsidering The PFS Debate

With all of the evidence in mind, here are our current perspectives on PFS:

- PFS is likely real, but also probably affects fewer than 1 out of every 5,000 to 10,000 finasteride users.

- If PFS is real, its prevalence is likely overstated online due to negativity bias in public anonymous hair loss forums.

- While many people claiming PFS might instead be suffering from a psychological disorder, we’ve spoken to people alleging PFS who (1) are otherwise healthy, (2) have no psychiatric disorders, (3) have successful careers, (4) have good relationships with friends and romantic partners, (5) have never filed a lawsuit against Merck, (6) have received a PFS diagnosis by a doctor – sometimes with corroborating histological data, and (7) just want their life to go back to normal. For these reasons, PFS reports from credible individuals need to be separated from the hysteria, rather than dismissed by way of lumping in with the hysteria.

- Anyone considering finasteride should be made aware of the debate surrounding post-finasteride syndrome.

- At the same time, with a small estimated prevalence of PFS, those with AGA should consider the risk-benefit analysis of finasteride – especially in the context of what other behavioral risks people engage in on a daily basis.

PFS: Contextualizing Its Risk Vs. Other “Voluntary” Behavioral Risks

If you’re considering finasteride, but have decided against trying it because of concerns of PFS, we 100% understand.

With that said, let’s contextualize what a 1 in 5,000 (or lower) estimated risk of PFS actually looks like in the context of other risks you might take in your everyday life.

Throughout a lifetime, 1 out of every 102 Americans will die in a motor vehicle accident.[29]https://injuryfacts.nsc.org/ However, this does not stop the overwhelming majority of Americans from operating motor vehicles. While accidents are tragic and sometimes unavoidable, there are also safe-driving behaviors that might lower that risk, and in doing so, allow you all the benefits of driving.

We believe the same is true for finasteride and hair loss.

Consider the heavy psychological and emotional impact that hair loss can have (especially on younger people). Also consider the overwhelming clinical evidence on finasteride – a drug that can stop the progression of AGA in the majority of men, and for 10+ years. Now consider the debate over PFS and its loosely estimated prevalence of 1 out of every 5,000 to 10,000 finasteride users.

The decision to try or not try finasteride is entirely your own to make, along with the medical guidance of a physician. Depending on your needs, preferences, and goals – all of us will weight the above evidence and the opportunity costs of finasteride (i.e., more lost hair) differently. But if PFS is a top concern for you, we believe – much like safe driving – that there are ways to still benefit from the drug while also further lowering that ~1 in 5,000-10,000 risk.

If PFS Is Real, Can We Reduce Our Risks Of Developing It?

Currently, there are no risk factors (aside from psychiatric disorders) that might help to predict someone’s risk of PFS. But in our opinion, any strategy that might reduce side effects from finasteride may also reduce the risk of developing PFS.

By opting for lower-dose oral finasteride formulations, or by using certain topical finasteride formulations, finasteride users can not only reduce their total drug exposure over a lifetime, but also better localize the effects of the medication to the scalp.

Under both circumstances, we suspect there to be a significant risk reduction in both finasteride-linked side effects as well as PFS.

We hope this article helps, and if you’d like personal support on your hair loss journey, you can always partner with our team inside our membership community.

References[+]

References ↑1 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32033719/ ↑2, ↑21 https://www.karger.com/Article/Fulltext/497362 ↑3, ↑5 https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0022202X15529357 ↑4 https://www.oatext.com/Long-term-(10-year)-efficacy-of-finasteride-in-523-Japanese-men-with-androgenetic-alopecia.php ↑6 http://www.drproctor.com/propecia/propecia.pdf ↑7, ↑22 https://www.nature.com/articles/ncpuro1012 ↑8 https://www.fiercepharma.com/vaccines/whistleblowers-accuse-merck-of-withholding-info-on-mumps-vaccine ↑9 https://www.nature.com/articles/450324b ↑10 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3116931/ ↑11 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21557276/ ↑12 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34247957/ ↑13 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4137476/ ↑14 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK513329/ ↑15 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32951160/ ↑16 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6962501/ ↑17 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7354335/ ↑18 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3997870/ ↑19 https://www.amjmed.com/article/S0002-9343(06)00689-9/fulltext ↑20 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8254833/ ↑23 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23067029/ ↑24, ↑26 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2929552/ ↑25 https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamadermatology/article-abstract/478759 ↑27 https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0190962298700076 ↑28 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4017493/ ↑29 https://injuryfacts.nsc.org/ Want help with your hair regrowth journey?

Get personalized support, product recommendations, video calls, and more from our researchers, trichologists, and PhD's dedicated to getting you the best possible outcomes.

Learn More

Perfect Hair Health Team

"... Can’t thank @Rob (PHH) and @sanderson17 enough for allowing me to understand a bit what was going on with me and why all these [things were] happening ... "

— RDB, 35, New York, U.S.A.

— RDB, 35, New York, U.S.A."... There is a lot improvement that I am seeing and my scalp feel alive nowadays... Thanks everyone. "

— Aayush, 20’s, Boston, MA

— Aayush, 20’s, Boston, MA"... I can say that my hair volume/thickness is about 30% more than it was when I first started."

— Douglas, 50’s, Montréal, Canada

— Douglas, 50’s, Montréal, CanadaWant help with your hair regrowth journey?

Get personalized support, product recommendations, video calls, and more from our researchers, trichologists, and PhD's dedicated to getting you the best possible outcomes.

Join Now - Mission Statement